- Home

- Steve Alten

The Firehills Page 8

The Firehills Read online

Page 8

Once she had found a formula that would work, she paused, breathing deeply, centering herself. And then, with her arms thrown wide to the moon, she cried out:

I invoke thee and call upon thee,

Mighty Mother of us all,

Bringer of all fruitfulness; by seed and root,

By bud and stem, by leaf and flower and fruit,

By life and love do invoke thee to descend upon the body of this,

Thy servant and priestess.

She stopped, heart pounding, eyes closed. The feeling of standing upon a precipice grew stronger, making her head spin. Taking a deep breath, she continued:

Hail Aradia!

From the Amalthean horn

Pour forth thy store of love;

I lowly bend Before thee, I adore thee to the end,

With loving sacrifice thy shrine adore. Um.

She stumbled. The rite called for incense, and she had none. She would have to skip a bit.

Tum-ti-tum, spend thine ancient love,

O Mighty One, descend

To aid me, who without thee am forlorn.

Her head was pounding in time with her heartbeat, and she felt the sweat cool on her skin in the night breeze. She seemed to feel everything more intensely—the movements of the tiny hairs on her upraised arms, small scurryings in the grass, the sharp smell from the sea far below her. She shook her head, trying to find a still point of concentration from which to continue. One last verse, to seal the ritual, to give it its power. Ignoring the waves of sensation sweeping over her, she made the shape of a pentagram in the air above her and called out:

Of the Mother darksome and divine

Mine the scourge, and mine the kiss;

The five-point star of love and bliss

Here I charge you with this sign.

Nothing. And then a silent explosion, a detonation without sound or force, felt only in her mind. Charly staggered and turned around. The hillside behind her was a blaze of golden light. A flame had sprung from every flower of the gorse, a million tiny candles burning clear and bright in the darkness. The sweet smell of coconut was overpowering. She gasped, her face bathed in the yellow radiance as the Firehills poured their tribute into the night sky. Moving her head to take in the spectacle, Charly found that her vision was blurred. No, not blurred—doubled—as if everything she saw bore an overlay, another layer of meaning drawn across the everyday world like a veil. Nothing was clear or familiar anymore. Turning back, it seemed as if the sea had retreated, for she was now some distance from the shore. A tumbled expanse of rough grass and blazing gorse ran down to a cliff edge, beyond which she could hear the relentless boom and hiss of the waves. Sensing some presence, she spun around. Behind her was a steep slope. The blazing flowers of the gorse were still there, but another landscape lay over them, older, darker. High up on the skyline, a fire was burning, a plume of sparks streaming away on the steady wind from the sea. A beacon, she thought, the Firehills!

Charly could hear music, rhythmic drums and the chanting of human voices. The sense of doubled vision made it hard to focus, but she seemed to see a figure moving toward her, picking its way between the dark backs of the gorse bushes.

Charly closed her eyes and took a deep breath, trying to clear her head. When she opened them again, the figure was much closer—a young woman, tall and darkhaired. She was dressed in the clothes of a woodsman or hunter, linen and leather, earth colors, and the light of the moon seemed to cling to her as she walked.

The sensation Charly had before, of heightened senses, was overwhelming now. She heard, felt, saw everything so clearly. A smell of wood smoke from the beacon on the hill, though the wind was blowing away from her. Again, she felt the tiny stirrings of the fine hairs on her arms. She felt the pounding of the distant drums through her feet as much as she heard them.

“Daughter,” said a voice.

‡

“Now then, young Sam,” said Wayland, “finish up yer snap and let’s set to.” The huge smith was bustling around his workshop, gathering together various items. Sam stuffed the last of the bread and cheese in his mouth and stood up, dusting the flour from his hands and clothes.

“I’d make ’ee a sword,” continued Wayland, “but it’d be awkerd for ’ee ter swing about, bein’ a little ’un. Besides, ’tis the virtue of the iron’s the thing, not the size o’ the blade. Can’t stand any touch o’ the stuff, the Faery Folk. No, we’ll make ’ee somethin’ more suited to yer size.”

He brought forth from the recesses of the room a dull, grayish bar of metal, a little shorter than Sam’s forearm.

“Aye, this’ll do,” he said, eyeing the metal thoughtfully. “I ’ad a mind ter make summat special wi’ this. A day and a night I worked on this”—he waved the bar at Sam—“’eatin’ it over charcoal, drawin’ it out, foldin’ it, ’eatin’ again. Takes up some o’ the goodness o’ the coal, see? Stops it bein’ brittle. Aye, this’ll do just right.”

He took the length of metal over to the great open hearth, where charcoal was glowing gently in the gloom.

“Your job, lad,” said Wayland, “is ter tackle to with the bellows.” He gestured toward a contraption of wood and leather beside the hearth.

Sam made his way over to where the smith indicated and was hit by a wave of intense heat. Squatting down, he grasped a sweat-polished wooden handle and gave it an experimental tug. As it moved downward, there was a deep whoosh, and the charcoal in the hearth glowed yellow. Sparks rushed upward, and the heat almost knocked him over backward.

“Right, lad,” said Wayland, “just keep it up.”

Sam raised the handle and brought it down once more and again. The charcoal flared, the air shimmered, and Sam settled into the rhythm.

Using a pair of tongs, Wayland placed the length of iron in the fire, at its very heart where the coals glowed almost white. He turned it from time to time, studying it closely, until it too began to glow. When he was satisfied with its color, he took it over to a great anvil mounted on a block of wood and began to hammer. Working along the edges, always in the same direction, Wayland began to draw the blade out, creating a taper from hilt to tip. From time to time, he returned the metal to the fire and waited until the cherry glow returned.

The sweat began to drip from Sam, running down his nose, and he was grateful when Wayland returned the blade to the anvil, so that he could rest his aching arms. The heat and the clangor of the smith’s hammer made the air pulsate. And so the hours passed: Wayland intent on his work, his face screwed up in concentration in the ruddy glow of the coals, while Sam alternated between intense activity and periods of boredom. He crouched in the half-light, his hair plastered to his head with sweat as the smith performed his craft.

Occasionally, Wayland would heat the steel to a fierce glow, urging Sam to greater efforts, and then leave it to cool.

“Let it rest awhile, lad. And us, too. Reckon we’ve earned it.”

As they rested, Wayland explained to Sam the magic of the bladesmith’s trade, how the properties of iron varied according to its composition and the way it was heated, and how the rate at which the iron cooled also affected its quality. An ideal blade, he explained, should be hard enough to keep a sharp edge and yet not so hard that it became brittle and shattered. But it also should be flexible, but not too flexible or it would buckle or lose its edge. And the only way to judge was by experience—by the feel and look of the metal as it heated and cooled, by the way it responded to the hammer.

Then they returned to their labors. Sam toiled away at the bellows handle as Wayland reheated the blade and took it back to the anvil, the sparks leaping as he smote it with his hammer. In the long, hot darkness, the blade took shape—its final outline slender and smoothly tapered, with a metal rod at one end to take the hilt and pommel.

“Time to anneal it,” said the smith and placed the metal back in the flames. When it was glowing from end to end, he removed it, wrapped it in pieces of sacking smeared with wet clay, an

d laid in the embers of the fire.

“We’ll leave ’un there. Come back in the mornin’.”

‡

Charly looked up. “Who are you?” she asked. In the years that followed, she rarely spoke of this night, and it was largely because she could never find the words to describe the young woman who stood before her. She was beautiful, more beautiful than anyone Charly had ever seen or heard of. Her skin seemed to glow as if lit from within. Her hair was dark brown and worn in braids, pulled back and gathered behind her head by a bronze pin. She bore a raven on her shoulder. It gazed at Charly along its bristly beak, head on one side, and uttered a low croak. But it was the woman’s eyes . . . Charly could never find the words to describe her eyes. They drew her in, the irises of green and hazel spiraling inward to pupils of blackest night. And there, in that darkness, the stars.

“I am Epona,” said the voice, and Charly gasped. Epona! A name from her earliest dreams. Although her initiation had come upon her unexpectedly and rather earlier than was usual, Charly had been a good student. She had read her Book of Shadows, handed down to her by her mother, and many of the other classical texts on the mysteries of Wicca. Many of these dealt with the various aspects of the Great Goddess, the many names by which the one mother goddess had been known in the cultures of the ages, Greek, Roman, Egyptian, and so on. One of Charly’s favorites had always been Epona. She was a horsegoddess of the ancient Celts, a goddess of the Underworld but also of healing and the harvest. She was the only Celtic goddess to have been worshipped in ancient Rome, having been adopted by the Roman cavalry, who discovered her as they fought their way through western Europe. To Charly, brought up on a farm, she had always seemed the ideal goddess, wild and young, a friend to the farmer and to the rider.

“Come,” said Epona, “ride with me.” She whistled and was answered by a high whinny. A thunder of hoofbeats and a white stallion appeared. It stamped to a halt before them, the breath gusting from its nostrils, blue white clouds in the moonlight. Epona mounted and beckoned for Charly to join her. The raven had flown as the horse approached, drifting silently into the night on soot-black wings. Reaching out for the offered hand, Charly experienced a swirling sensation and found herself on the horse’s back, clinging to Epona’s waist.

With a mighty kick, the horse took flight, cantering up the slope. As they picked their way through the bushes, the thorns scraping Charly’s legs, she saw that they were heading for the fire on the hill’s summit. The sound of chanting grew louder. At the foot of the beacon, Epona reined in the horse. It pranced sideways for a moment, reluctant to end its flight. The raven circled them once, then flopped to the ground, hopping out of the reach of stray hooves. Charly looked out over the sea.

“I heard the words of the old ritual, child,” said Epona.

“You are yet young.”

“I–I know. I’m sorry,” stuttered Charly. “I was desperate.”

“What is it you seek?”

Charly thought for a moment. “Power.”

Epona threw back her head and laughed, a wild sound. The horse reared, and Charly clung to the goddess.

“Power? You are a child. What need have you for power?”

“A friend of mine is in trouble. I need to help him,” replied Charly sharply.

Epona laughed once more. “Come,” she said and with another blur of sensation, Charly found herself on the ground once more, Epona by her side. Looking around, she saw that the horse was gone. Only the raven remained, and with three flaps of its glossy wings, it returned to Epona’s shoulder.

The goddess took Charly by the hand and led her to the foot of the beacon. They stood side by side, the great fire roaring above them, the sparks streaming away inland on the wind. Before her the land dropped away, and still Charly had the impression of two worlds, one layered upon the other. Dimly, she could still make out the blazing flowers of the gorse, in the Firehills of her own time. But over them lay another landscape, one much older. As she had noticed before, the sea was much farther away than she remembered. How many centuries, she wondered, would it take for the waves to erode that much land?

Charly saw that Epona was beckoning and moved to follow her. It was difficult to walk. Her doubled vision caused her to stumble as she struggled to keep up with the horse goddess. Cresting the ridge, she paused. Below her, in the lee of the hill, was a hollow. The sound of drums and chanting was coming from a group of huddled figures, their shadows flickering in the light from the beacon. Charly moved closer. As she drew near, the figures were revealed as men in rough clothes of linen and leather, heavy cloaks of animal skin drawn close about them. They bent over something hidden from Charly, some chanting, some beating wide, shallow drums of tanned hide.

“Come closer,” said Epona, beckoning. “Do not be afraid.”

‡

Sam awoke scratching. He had spent the night on a rough mattress stuffed with straw, in the single room that Wayland shared with his son. Rolling his shirt up, Sam examined the rash that dotted his stomach and chest. He hoped this was from the prickling of the straw, but he suspected that some kind of insect had been involved. After a breakfast of fresh eggs and more coarse bread, Wayland said, “Now then, lad. Let’s see ’ow she’s farin’.”

He set off toward the smithy.

Sam arrived to find the smith lifting the bundle of sackcloth from the cold ashes of the forge and peeling back the layers. The clay had baked solid, and the cloth crackled, shedding clouds of dust as he revealed the contents. Sam reached out and touched the smooth surface. The iron was black and cold now, a dull spike of dark metal marked with the imprint of Wayland’s hammer.

“C’mon, boy,” said Wayland. He began to build a fire in the center of the forge, heaping charcoal over a pyramid of dry sticks. Sam helped him, and soon they were both covered in black dust, grinning at each other with dazzling eyes and teeth. Wayland struck a spark into a tuft of dry moss, blew on it until a glow bathed his face, and fed it into a gap in the pile of firewood. After more blowing, a tiny flame sprang into life. While Sam watched the fire, the smith worked on the blade with files, grinding and shaping, adding the beginnings of a sharp edge. The metal was soft, easily worked, and quickly took shape under Wayland’s expert hands.

The fire blazed for a while, lighting up the dark smithy, then began to settle. With a brittle tinkling, the charcoal collapsed into the embers of the wood and the flames subsided. When the hearth was glowing gently, Wayland added more charcoal and said, “Right, lad. Get on they bellows.”

Sam hauled on the bellows handle until the charcoal roared, and Wayland returned the blade to the fire. “Need to ’arden it now,” he told Sam. “Get pumpin’.”

‡

Charly gasped, her hand to her mouth. As she drew closer to the circle, she saw that the men were bent over a shallow pit in the earth. Within lay a body, a tall man of middle years, a dusting of gray in his hair. His arms were folded across his chest, and beneath his hands was the pommel of a long sword. He was strewn with the petals of wildflowers, and items of jewelry had been placed about him. Around his neck was a chain of bronze links, and in his hair, clasped to his brow, was a circlet in the form of galloping horses.

“They pray to me now, at the time of death,” said Epona, “for the Underworld is mine. You say you seek power. This is power.” She gestured at the chanting circle. “The worship of men.”

“But that doesn’t help me,” protested Charly. “Nobody worships me. I’m just a kid.”

“No, my child,” replied Epona, “for you drew down the moon. The Goddess is within you now. Take up your power.”

She led Charly by the hand into the center of the circle. They seemed to pass through the bodies of the men like smoke and found themselves standing by the graveside. The drumming and the relentless drone of voices crowded in on Charly. The two worlds, the ancient and the present day, swirled around her on black wings. She saw images, visions in the streaming sparks from the beacon fire—births, de

aths, the galloping of white horses on green fields, harvests of golden wheat, bright swords against the sky. The eye of the moon, high above now, seemed to pierce her, nailing her to the spot. She couldn’t breathe. And then, when she thought she would burst, Epona reached out and touched one finger to her forehead.

Suddenly, Charly was at the center of a shaft of light, a pillar of cold radiance that lanced upward into the night sky. She seemed to expand, until she filled the whole world, and the white light spilled out of her, from her eyes, from her mouth. Clenching her fists, Charly drew the radiance into herself, until it formed a white-hot core deep inside. She threw back her head and laughed, high and wild.

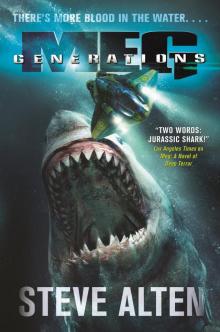

The Trench

The Trench Generations

Generations The Mayan Resurrection

The Mayan Resurrection Vostok

Vostok Grim Reaper: End of Days

Grim Reaper: End of Days The Omega Project

The Omega Project Domain

Domain Meg

Meg MEG: Nightstalkers

MEG: Nightstalkers The Mayan Resurrection mp-2

The Mayan Resurrection mp-2 Goliath

Goliath Undisclosed

Undisclosed Dead Bait 2

Dead Bait 2 Loch, The

Loch, The The Loch

The Loch The Firehills

The Firehills Sharkman

Sharkman The MEG

The MEG Phobos

Phobos Meg_A Novel of Deep Terror

Meg_A Novel of Deep Terror Meg: Origins

Meg: Origins