- Home

- Steve Alten

The Firehills Page 7

The Firehills Read online

Page 7

“Mum!” she began, “I’m OK. Don’t fuss—”

“Don’t fuss! I’ve—”

“I’ve been with Sam. We went to rescue Amergin.”

“You went . . . oh, terrific.” Megan raised her eyes to the ceiling. “So where are they?”

“Erm,” began Charly, “there was a bit of a problem.”

“Megan, Charly,” interrupted Mrs. P., “I think we should go and sit down, and you can tell us what happened.” She ushered Charly through into the lounge. Megan ran one hand distractedly across her face, then followed.

‡

Five minutes later, Charly had finished her story. Silence fell. Eventually, Megan said, “What am I going to tell his parents?”

Charly stared at the floor.

“I don’t believe this is happening,” Megan continued.

“At least, Amergin is an adult—there’s a chance he can look after himself. But Sam . . . ? How could you be so stupid?” She gave Charly a despairing look. Charly felt tears spring to her eyes once more.

“Megan, dear,” pleaded Mrs. P., “don’t be too harsh on the child.”

“I’m going to my room. I need to think.” Megan stood up. “You, young lady, are so grounded—” She paused, then turned and marched out of the room.

Mrs. P. stared at Charly for a long moment. “Foolish and headstrong,” she said. “And utterly reckless.”

Charly screwed up her eyes and tried not to sob.

“And you’re not much better,” continued Mrs. P.

“Huh?” Charly looked up.

Mrs. P. was smiling. “Your mother, dear,” she continued. “She was just like you, when she was your age. But not quite so talented. Don’t take it too hard—she’s upset and frantic with worry. I’ll go and speak to her soon, see if we can come up with a plan. You go up to your room, and try to get some rest.”

Charly nodded, wiped her nose on her sleeve, and headed for the stairs.

‡

Sam scrambled to his feet, ready to run. He was on a grassy slope, dotted here and there with scrub. A featureless sweep of grass stretched before him up to a clear blue sky. He walked up the slope a short way, but the turf was unmarked, featureless, apart from a scatter of dry sheep dung. It seemed unlikely that elves or fairies were going to burst out of the ground.

He turned around, and his eyes widened. The ground dropped away steeply, the scrub growing thicker toward the foot of the slope and merging into the fringes of woodland. A woodland that rolled away in all directions, a dense green rug thrown across the landscape, fading to the palest blue haze on the distant horizon. Here and there, a faint plume of smoke rose from a clearing, marking a hidden farm or village. But otherwise the trees had dominion, an ancient forest like nothing Sam had ever seen. Well, he thought to himself, no sign of Hastings.

One of the plumes of smoke was close, no more than an hour’s walk, Sam guessed. With no better plan, he descended the slope, scrambled over a rough hurdle fence, and set off into the trees.

From his view on the hillside, Sam had been expecting some sort of primeval wildwood, a tangle of thorns and brambles, but the forest was surprisingly open. Many of the trees had been cut at the base and left to regrow, craggy old stumps of hazel and hornbeam sprouting crops of tall, straight shoots, leaves fluttering like flags in the breeze. Here and there, a mighty oak or ash had been left to grow tall, great timber trees standing like pillars with their crowns in the sunlight.

Sam soon picked up a rough path that meandered between low banks studded with wildflowers. It was bluebell time, and the ground to either side of the path glowed beneath a blue haze. The air was heavy with the perfume of a million nodding blooms.

As he walked, he became more than usually aware of the presence that always seemed to lurk behind his mind, peering through his eyes. The spirit of the Green Man within him recognized this place. It was the world where he had been born, the ancient wildwood where he had grown and flourished before humans, spurred on by the whispers of the Malifex, had destroyed it. The spirit seemed to push forward, until Sam felt as if someone were standing very close behind him, so close that if he turned and looked, they would be eye to eye. He heard, or felt, a chuckle—a deep current of mirth running through his head. Beneath the laughter was something wild, primeval, the music of pipes and the distant sound of horns. Sam broke into a run, flickering through the shafts of light that pierced the high canopy. The fierce happiness of the Green Man swept over him, and he began to shift from one shape to another for the simple joy of it. He was a hare once more, a wolf, a polecat arcing through the long grass like a coiled spring.

Once he heard a snorting and rustling and feared that the Sidhe had returned. But it was only a herd of pigs, rooting beneath the oaks. They were leaner and hairier than the fat, pink animals Sam was used to, with a halfwild look to them. They ignored Sam, seeing only a young stag, and he moved on.

He passed a fallen tree, a giant of the canopy that had succumbed to gales or rot and had crashed down into the undergrowth. Its roots had taken with them a huge disk of earth, which stood now vertical, leaving behind a circular crater. The rain had filled it, and the creatures of the forest were busy claiming this new pond as their own. Yellow irises flowered around the edge, and kingcups, and the blue needles of damselflies darted through the rushes. In a grassy clearing, Sam stopped before an area trampled to mud by deer and assumed his human shape. A huge butterfly, dark except for a lightning-flash of white across its wings, fluttered up from a hoofprint. Its wings glinted an intense metallic purple as it passed through a shaft of sunlight, heading up to the high canopy of oaks. Sam was getting hungry. He had lost all track of time, but it felt like several hours since his last meal. He stopped for a breather, climbing the low bank and settling with his back against a tree. He sat listening to the sound of birdsong for a while, watching midges weave a ball of silver in the light that fell on the path below. And then, with nothing else to do, he continued on. Soon he came to a patch of woodland that had recently been cut—the word coppiced sprang to his mind, though he wasn’t entirely sure what it meant. Here the old stumps that he had seen throughout the forest had had their crop of tall stems removed, and piles of long poles were neatly stacked by the path. The great timber trees had been left to grow on and stood in majestic isolation in the wide clearing. Sawdust and wood chips littered the ground, but already primroses and purple orchids had pushed up through, basking in the unexpected flood of light that now bathed the forest floor.

A little farther on, Sam came across a series of low mounds. They reminded him of barrows or tumuli, but the earth was raw and fresh, and each was crowned with a wooden peg surrounded by turf. A wisp of smoke drifted from around one of the pegs. Sam went over to investigate. He placed one hand on the bare clay of the mound and found that it was warm. Moving on, he soon found an explanation for the mounds. They were charcoal kilns—the last in the line had been broken open and its contents removed. Glossy black charcoal was strewn across the trampled ground, and a pile of blackened logs stood to one side. He kicked at the scraps of charcoal, and they tinkled like glass. The trail of footprints and black dust led off through the trees, and Sam’s eyes, following the trail, made out the dark shapes of buildings in the distance.

Sam edged into the clearing, eyes darting back and forth. A regular metallic ringing came from the largest building, as did the plume of smoke that he had seen from the hillside. The buildings themselves confirmed his suspicion. This was not his own time. Thatched and timberframed, the sides daubed with mud and straw, these were no buildings from Sam’s world.

There were three main structures: the largest in front of him, across a yard of bare earth, and two smaller ones—barns or storehouses of some sort—to either side. A few hens scratched around in the dust. The trail of charcoal fragments led to a neatly stacked pile of black logs by the main building. The metallic sound of hammering suddenly ceased, and a figure appeared at the door of the building ahead, a hu

ge hulk of a man. He stared at Sam for a few moments, then beckoned, turned, and disappeared back inside. Sam stood on the edge of the yard, paralyzed with indecision. The man had not seemed hostile. Otherwise, surely, he would have approached Sam instead of turning back. But was it safe to follow? Sam considered his options. He had clearly emerged from the Hollow Hills far from his own time. He was alone, with no idea of where or when he was or how to return. What did he have to lose? With a shrug, he set off across the yard.

It took a few moments for his eyes to adjust to the gloom. The windows were tiny, and the main source of illumination was a roaring fire in the center of the room. Silhouetted against its light was the bulk of the man who had beckoned. He had his back to Sam and was examining something intently.

“Welcome, lad,” he rumbled, without turning around. His accent was thick but somehow familiar. “Don’t ’ee ’ang on the threshold. Come on in.”

Sam realized that he spoke like the man they had met at the foot of Windover Hill, who had told them of the windsmith. He stepped forward.

The man turned suddenly, and Sam saw that he was holding a long, curved blade. In a panic, Sam scuttled backward and collided with the doorframe, bringing down a shower of dust from the thatch.

“Oh, don’t ’ee mind this,” said the man, waving the blade at Sam. “New scythe blade; old ’un’s as sharp as I am.” He placed it carefully on a low wooden table.

“Run on an’ get us summin’ t’eat,” he commanded. Sam was confused for a moment, but then a small shadow detached itself from the larger gloom and scurried past him. It was a young boy, covered in soot. Sam had a glimpse of wide, white eyes, and then he was gone.

“Don’ get many strangers,” said the man, folding his arms across his massive chest. He was wearing a long leather apron over rough brown leggings. His arms were bare and hugely muscled.

“I’m, er, lost,” said Sam.

“I should say y’are,” agreed the man, “a tidy way lost, an’ all. A young ’un, too, ter be wanderin’ the ’ollow ’ills.”

“You know about the Hollow Hills?” Sam asked in surprise.

“Course I do, boy! I ain’t no gowk! An’ I knows a Walker when I sees one.”

“A walker?”

“A Walker Between Worlds. One as uses the ’ills to get about, an’ ’as commerce with the Faery Folk.”

“I dunno about commerce, ” replied Sam. “I was trying to get away from them. They’ve kidnapped my friend.”

“Ah, a sorry tale,” said the man with a sigh. “Not wise to cross ’em, the Farisees. What did ’e do, this friend of yourn?”

“He invaded their land, killed quite a few of them, drove the rest underground.”

“Ah. ’E’ll be a pop’lar lad, then.”

At that moment, the boy returned with wooden plates bearing thick slabs of coarse bread and slices of tangy cheese.

“Tuck in, lad,” said the man.

“Thanks. I’m Sam, by the way.”

“’Ow do, Sam? You can call me Wayland.”

Silence fell as they applied themselves to the food. Eventually, Wayland said, “Youm gonna rescue ’im, then?

This friend of yourn?”

“That was the idea,” admitted Sam, “but I didn’t get very far. I’d just found a way into the Hollow Hills when the Sidhe turned up, and then somehow I sort of fell out and ended up on a hillside not far from here.”

“Aye, well, them as goes crawling round in the earth like moldywarps is arskin’ fer bother.”

“Moldywarps?” spluttered Sam, spraying crumbs.

“Little gennlemen in black velvet, as digs in the earth. Leaves their little mounds o’ muck hither and yon.”

“Ah, moles,” said Sam and returned to his sandwich. Wayland was quiet once more, chewing steadily. His face was weather-beaten and ruddy, like old leather, polished and oiled; and his graying hair was square-cut at the shoulders. His blue eyes twinkled in nets of fine lines as he watched Sam.

“Iron,” he said, after a while. “That’s yer lad for the Faery Folk. Iron.”

Sam looked blank.

“Can’t stand it, see?” Wayland continued. “Takes away their power, only thing as can kill ’em. You needs you some iron.”

“Have you got anything I could use?” asked Sam. Wayland dissolved into laughter. It went on for what seemed like an unreasonable length of time, and Sam was starting to look around in embarrassment when Wayland took a shuddering breath, wiped his eyes, and said, “’Ave I got any iron? I’m a blacksmith, boy! I’ve got precious little but iron! Tell ’ee what, you an’ me, we’ll make somethin’, a good ole pigsticker fer visitin’ bother on the Farisees!”

The smith jumped to his feet. “Don’t just sit sowing gape seed, lad. Tackle-to!”

‡

Charly lay on her back on her bed, staring at the ceiling. Her mother had gone upstairs with Mrs. P., up into the attic room, where they were now deep in discussion. Closing her eyes, she pictured once more the crop circle forming around Sam, the spheres of light crackling and dancing, the breathtaking pattern of swirls stamped across the landscape. How typical of Sam, she thought. Miracles and wonders followed him wherever he went, and he blundered around in the middle of them, moaning and sulking like a child. He was a hero, yes. He had defeated the Malifex, after all—but almost by accident. She had done most of the real work. And Amergin, of course. She sighed. It all came down to power again. Sam was a boy and had it; she was a girl and didn’t. If only there was some way. . . . She thought again about her initiation and the books she had read as part of her training. Her Book of Shadows was full of tantalizing hints and rumors of the powers she would gain as she completed her training. One ritual in particular had always stuck in her mind, because it summed up the glamour of Wicca. It was central to the Craft and was carried out by the high priestess. Charly shivered just thinking about it. From her earliest memories, she had dreamed of one day becoming a high priestess, with her own coven. An idea came to her and she sat up.

Her mother would go crazy. She felt sick when she thought of how mad her mother would be. But then she thought of Amergin and Sam and of how she had encouraged Sam to set off on his rescue mission. Her mind was made up. She jumped off the bed and ran over to the window. The sun was setting off along the coast, its light glinting on the sea far below. Charly threw open the window and breathed in the salt tang of the air. Closing her eyes, she concentrated on a shape. It was becoming easier with every attempt. Moments later, a seagull flicked its white wings and headed into the east.

CHAPTER 5

The sixty-five ships of the Milesians rode the swell off the coast of the new land, their tattered sails furled now. Amergin stood in the prow of the leading ship, one foot braced against the gunwale, and looked out over the expanse of green. As his eyes took in the rolling hills where the cloud shadows raced, his heart felt as though it would burst with joy. A song came to him—

Amergin. I know you can hear me.

An insistent pressure pushed against the edges of his mind. Go away, he thought, this land is ours. Amergin. Stop it, now. You’re wasting your time. Again, the pressure, making colored lights dance behind his eyes. And then a searing pain that brought him gasping into consciousness.

That’s better, said the Lady Una. You can’t hide in your memories forever.

“My lady,” croaked the wizard. He had neither eaten nor drunk for many hours now, perhaps days. It was impossible to tell in the darkness of the cavern. He peered down at the ghostly oval of Una’s face, floating in the gloom below him. He was suspended in midair, far above the floor of the chamber, by a webwork of pale blue energy that crawled and writhed over his skin. His arms and legs were flung wide, and the pain in his joints was becoming unbearable. He was kept aloft by the will of a circle of faeries, crouched around the perimeter of the cave. They worked in shifts. Whenever one of the circle grew tired of their mental efforts, that one would be replaced.

“Amergin, my dea

r,” said the Lady Una, using conventional speech rather than her mind, “your defenses are weakening; I can feel it. But you could end the pain now, so very easily. Simply tell us what we want to know.” She sat on the ground beneath him, knees tucked up beneath her chin, and smiled sweetly. “What—or who—is this force that opposes us? And how can we overcome it, to claim the power of the Malifex?”

But Amergin had gone. In his mind, he was splashing through the surf, side by side with Eremon and Emer Donn, up onto the shores of Ireland.

‡

With the setting sun at her back, Charly left the buildings of Hastings behind her and headed out over wilder country. Wheeling over a crumpled landscape of woods and valleys she searched, straining to find a familiar landmark. Normally, she would have been lost, but in this body, she could draw upon senses that would bring a bird safely from Africa to its particular nest site each year, across a thousand miles of sea. Skimming low over the cliffs, something came to her—a particular combination of smell, sight, senses she couldn’t even name. Together, they cried out to her: Here!

Here was the place she was seeking, Mrs. P.’s special place, the Firehills, where her initiation had taken place. Tumbling from the sky, she landed in the long shadows of the gorse bushes and resumed her human shape. She walked farther down the hillside, toward the sound of the waves. Her heart was thumping in her chest, but she was torn between fear and excitement. She felt as if she was on the brink of something, something wonderful but scary, like a roller-coaster ride. All she had to do was take the next step, and she would be whisked away into the night, soaring and plummeting.

In an open glade of grass among the dark mounds of gorse, she stopped. The moon had risen now, close to full, and its light cast a track of pale gold across the sea. Charly took a deep breath. Right, she thought, let’s see what I can really do. What she was about to attempt was not strictly forbidden—Wicca had few rules beyond its Rede: An it harm none, do what thou wilt. However, there were traditions, ways of doing things. And this was not one of them. Charly had decided to carry out a ceremony called Drawing Down the Moon. In this ceremony, the high priestess of the coven receives the spirit of the Goddess, in effect, becomes the Goddess, for the duration of the rite. Since Charly was neither a high priestess nor currently part of a coven, this was unusual to say the least and not without risks. But to rescue Sam she needed power, and this was the fastest way she could think of to obtain it. The ritual was clear in Charly’s mind. She had memorized it long ago, dreaming in her bedroom of the day when she would be a high priestess, wise and graceful, leading her coven in the ways of the Craft. However, since the ritual generally involved several people, she had to frantically edit the words in her head.

The Trench

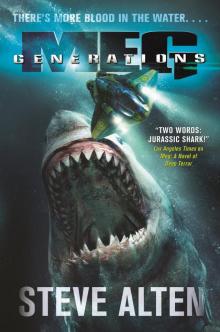

The Trench Generations

Generations The Mayan Resurrection

The Mayan Resurrection Vostok

Vostok Grim Reaper: End of Days

Grim Reaper: End of Days The Omega Project

The Omega Project Domain

Domain Meg

Meg MEG: Nightstalkers

MEG: Nightstalkers The Mayan Resurrection mp-2

The Mayan Resurrection mp-2 Goliath

Goliath Undisclosed

Undisclosed Dead Bait 2

Dead Bait 2 Loch, The

Loch, The The Loch

The Loch The Firehills

The Firehills Sharkman

Sharkman The MEG

The MEG Phobos

Phobos Meg_A Novel of Deep Terror

Meg_A Novel of Deep Terror Meg: Origins

Meg: Origins