- Home

- Steve Alten

Vostok Page 6

Vostok Read online

Page 6

Inverness, Scotland (Associated Press)

Nessie may be gone, but the legendary monster that once inhabited Loch Ness appears to have left behind a hungry relative. According to eyewitnesses, a large water creature has been spotted stalking deer as they cross the waterway at night.

The monster’s latest kill occurred sometime Thursday evening. Invermoriston resident Esther Jacobs said she was walking along the shoreline of Loch Ness around sunset when she saw a disturbance in the water some twenty meters away. She later discovered the remains of a 290kg male elk washed ashore on the western bank, its hindquarters devoured in what appeared to be a single bite. “It was gruesome,” said Jacobs. “Thankfully this particular monster prefers to stay in the water, or my life might have been in danger.”

Dr. Rehan Ahmed, a marine biologist specializing in ancient sea creatures, was on hand to examine the kill. He agreed that this particular species probably measured more than twelve meters, but preferred not to speculate on whether it could be a plesiosaur. Ahmed and his colleague, Dr. Ming Liao, had arrived in the Highlands Tuesday evening from Antarctica for a special conference at Loch Ness’s new five-star resort, Nessie’s Lair. They were joined by George McFarland, an engineer out of Texas who works for Stone Aerospace. McFarland suggested underwater drones might be the best way to identify the species of this new Loch Ness Monster, though Esther Jacobs and other eyewitnesses claim the creature is not shy about surfacing by day. Said Ms. Jacobs, “With the tourist season approaching, it’s just a matter of time before someone videotapes the beastie.”

Liao gritted her teeth. “Bastard even managed to get in the name of his hotel.”

“This isn’t just a local story,” George said. “Those reporters last night spoon-fed this to the Associated Press. Our names are all over this.”

“Once I get the signed agreement from Dr. Wallace, it won’t matter. His presence at Vostok will quash this story.”

Ben chuckled. “Wake up, Ming. Zachary Wallace lost his nerve years ago. He has no intention of signing on to Vostok or any other underwater expedition, and his old man knows it. Angus Wallace played you; he planned this whole Loch Ness Monster story the moment we landed.”

“I don’t understand.”

“Tourism died with the monster, and last night the three of you helped bring it back to life. While you thought you were wooing Angus, the old man was baiting you, distracting you with false promises to get you to Invermoriston to see that carcass. Your presence last night served to validate the hoax and give his story legs—no pun intended. And the beautiful part is you paid him five thousand dollars to do it.”

5

Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned.

—Male proverb.

There is a saying among Highlanders that translates to “a tale never loses in the telling.” Angus must have repeated his tale a hundred times that first week, relishing how he had conned the “Asian harlot” out of five thousand U.S. dollars while priming the pump of tourism in the Great Glen.

To keep the momentum going, the Highland Council voted to use an infusion of grant money coming from British Parliament to install thirty visitor perches around Loch Ness. Each ten-foot-high covered platform would house three high-powered mounted telescopic cameras that ould allow tourists to snap downloadable photos of anything that crossed the lens of their viewport. Meanwhile, Alexander MacDonald, the Council’s new provost (and second cousin to Brandy and True) held a press conference to announce an international symposium, scheduled to convene at my father’s resort April 15 through April 22 to determine what this aggressive new species was. The Council extended invitations to marine biologists, cryptozoologists, and amateur monster hunters from around the world, with all resort guests receiving free passage aboard nocturnal voyages that would attempt to film the creature feeding on deer as the herds crossed the loch.

Reports of new sightings and photos purportedly taken by locals drove the story like a social media tsunami. Within weeks every hotel and bed-and-breakfast in the Great Glen was sold out for the season, led by Nessie’s Lair.

It was all great theater, except that now the public demanded to hear from the marine biologist who had not only identified the real Nessie two years earlier but had tracked it down and killed it. I was hounded twenty-four/seven, which made my life miserable and drew mixed reactions from the normally conservative administrators at Cambridge University.

Brandy, William, and I had been at Cambridge barely a week, living in a two-bedroom rented flat. Having arrived mid-semester, I was relegated to guest-speaking spots, rotating between undergraduate and graduate courses in oceanography and the marine sciences. The experience allowed me to re-acclimate to the academic environment, but the attention coming from my father’s escapades was affecting the student body’s perception of my role at the university—was Dr. Zachary Wallace a teacher or an entertainer?

And then a week before the Nessie’s Lair event, a serious-looking fellow entered my lecture hall, marched up to my lectern, and ceremoniously presented me with an envelope. Baffled, I opened it, my students bearing witness to the publicly staged event.

It was a subpoena.

“State your name for the record.”

“Angus William Wallace.”

The preliminary hearing was being held behind closed doors at the Sherrifs’ Court in Inverness. Present in the chamber was the judge, a court stenographer, my family, and a school of circling sharks in three-piece suits hailing from a law firm rated by England’s Legal Business magazine as the fifth most successful in all the United Kingdom. Judging from their number, it appeared as if they had summoned every attorney from their offices in Glasgow and Edinburgh.

If my father was intimidated by their full court press, he wasn’t showing it, but his barrister, my stepbrother, Maxie Rael, would need to change his underwear before the morning was through.

The lead litigator representing Dr. Ming Liao was a half-Italian, half-Ukranian man named Sam Mannino, who wasted no time going after Angus’s jugular. “Do you understand the reason for this preliminary hearing, Mr. Wallace? The purpose of our convening this morning is to share the strength of our case with your barrister, so he knows the extent of the shit-storm you created for my client and the lengths we’re prepared to go to make your life a living hell. For starters, we’ll be moving your very public trial from this cozy Sheriff’s Court in Inverness to the High Court in Glasgow in order to eliminate the biases of the plaid when we select a fifteen-person jury.

“On day one of the trial we will introduce evidence that shows you and your Highland Council cronies purposely deceived the public by concocting your little fairy tale about a second Loch Ness Monster. We will cross-examine the members of the Highland Council, effectually ending any future they might have had in holding an elected office, and then we’ll introduce Exhibit A—the tool your EMT used on the carcass of an elk—I believe it’s called a Jaws of Life—to make it appear as if the animal had been eaten. Then we will parade a day’s worth of experts before the jury to demonstrate how your antics and false promises regarding your son’s involvement in my client’s upcoming venture in Antarctica ruined her expedition, costing her millions of dollars in investment capital.

“And finally, after the jury reaches the verdict of your guilt in this little civil matter, we will take every asset you own, including the resort on Loch Ness—which Dr. Liao will personally burn to the ground. Worst of all, your fellow Highlanders will curse you and your clan until the end of days for the financial ruin your lies will deliver unto the Great Glen. And then, Mr. Wallace, then I’m going to push for criminal charges that will consume every waking moment of your barrister’s miserable life.

“How’s that sound to you, laddie?”

“Sounds as if yer skat momma’s still mad at me for defecating in her mouth the day ye was born.”

That didn’t go over well with the judge, but my father knew a dog-and-pony show when he saw one. I guess he figured

there was no harm in stepping in more shit before they presented their backroom offer to Maxie.

“They want you, Zachary. They want your signed commitment to copilot the submersible into Lake Vostok. In exchange, they will drop all charges, and there will be no press conferences to derail the symposium. Oh yeah—and your pay will be reduced by five thousand dollars to cover the money wired to Angus. As your barrister I strongly urge you to sign the papers so we can get the hell out of here.”

“You’re not my attorney, Maxie, you’re his.” I turned to Brandy and saw disgust in her eyes.

My father looked into my eyes and saw fear. “Oh, come on. It’s a bloody lake. Not like yer goin’ down in yer birthday suit.”

“Why does it seem like every time you’re in a courtroom, I get it up the ass?”

“Maybe ye like it there?”

“He’s all yours, Max. Come on, Brandy.”

“Come on where? Ye heard tha’ barrister. By the time they’re through humiliating yer father, no tourist in their right mind will come tae the villages. I’m none too happy aboot this, Zachary, but Angus is right—ye got tae go.”

“Listen tae yer wife,” the old man gloated.

“Shut yer pie hole, ye old bampot,” Brandy snapped. “Before my husband signs his name tae anything, I’ve a few conditions myself. First off, ye’ll be moving Alban intae the hotel immediately, so’s True can take proper care of him over the next five months.”

“The Crabbit… in my resort… the resort he cursed when we broke ground?” Angus was about to lose it when he saw the look in Brandy’s eyes. “Aye, whitever.”

“Second, when September comes ’round and it’s time for Zachary to go to Antarctica, True goes with him.”

Now it was my best friend who protested. “Me? In tha’ icebox for six months wit’ a bunch of boring old men? Are ye tryin’ tae neuter me, Brandy girl?”

“I’m trying tae neuter that Chinese vixen. Yer there tae prevent any alone time between Zachary and Dr. Liao before they descend intae that lake. So help me God, True MacDonald, if I hear my man so much as sits next tae her at breakfast, I’ll skin the two of ye alive—starting with yer short and curlies.”

5 months later …

6

August, die she must. The autumn winds blow chilly and cold;

September, I remember. A love once new has now grown old.

—Simon & Garfunkel, “April Come She Will”

13 September

For five months Vostok hung over my existence like a death sentence handed down by an oncologist. It greeted me every morning when I awoke, and it haunted my last thoughts before I succumbed to sleep.

What exactly was I afraid of? Being the anal-retentive left-brained thinker that I was, I mentally cataloged my fears into more easily digestible categories for self-analysis.

Fear of Separation: Six months would be a long time to be separated from my family. William was rapidly passing through infancy into the terrible twos, and each day seemed to introduce us to another facet of his burgeoning personality. I simply couldn’t get enough of him and arranged for my sabbatical from Cambridge to begin in June so I could spend the summer with him and Brandy back in Drumnadrochit.

I had read that Antarctic missions were especially hard on marriages, and mine was already strained. Though we had reconciled, it was painfully obvious that Brandy felt threatened by Ming’s combination of looks and intelligence. Not that my wife wasn’t smart or pretty—she was both. But she lacked a formal education and never had the opportunity to go to college, something Ming and I shared. As spring bled into summer, Brandy grew increasingly more temperamental, actually believing that my father and I had conspired to get her to accept my excursion to Antarctica by using the “infamous Wallace cunning.”

In her own way, Brandy eased my burden. By the time September rolled around I couldn’t wait to get out of earshot of her accusations—not a good way to part.

Was I interested in the exotic Dr. Liao? I’d be lying if I said there wasn’t an attraction, but Brandy was still my girl.

Then again, six months was a long time.

Back to my list.

Claustrophobic Fears: This was the dark cloud that had hung over my existence since I’d drowned and been revived in the Sargasso Sea. Despite Hintzmann’s assurances, the reality was that our three-man submersible would be smaller than the Massett-6, the sub that had cracked open at a depth of 4,230 feet.

Imagine taking a twenty-hour road trip without being allowed to stop and stretch. To prepare myself, I created a mini-sub cockpit out of cardboard and sat in it for three- to five-hour stretches. Willy would climb in my lap with his favorite book, Goodnight Moon, and we’d read together and fall asleep.

What can’t be simulated are the effects of a trillion-ton frozen ceiling of ice more than two miles thick. To reach Vostok’s frigid waters would require us to plunge down a laser-melted hole that would reseal behind us. The pressure capping our 13,100-foot-deep entry point would generate 4,000 to 5,000 pounds per square inch of pressure on our sub—a pound of pressure for every dollar Angus had been advanced out of my paycheck.

Thanks again, Pop.

Adding to my fear of enclosed spaces was the fact that, save for the sub’s internal displays and external lights, we’d be operating in complete blackness. If the power went out, or if we hit something, or if something hit us…

That last thought led to my final category of fear: Irrational Fear of the Unexpected. It included encounters with hydrothermal vents that spewed water hot enough to melt the seals on our sub and regressed into alien algae blooms that could clog our engines. And, of course, there were lake monsters.

Two years had passed since I’d nearly died in the jowls of one monster. Though I seriously doubted anything larger than a slug occupied Vostok’s waters, we would be entering an unexplored subglacial lake one hundred and forty miles longer and thirty miles wider than Loch Ness, energized by the same geothermal vents that had induced life on our planet 3.8 billion years ago.

Who knew what was down there?

A sane person would have walked away from this potential train wreck. Yet as much as I dreaded the trip, the scientist in me couldn’t wait to explore Vostok.

The more I researched it, the more I realized the lake was a gift to science and scientists throughout the world. To be among the first three humans to venture into its untarnished waters would cement my reputation forever.

Named after the Russian outpost established in East Antarctica in December of 1957, Lake Vostok was first theorized by a Soviet scientist named Peter Kropotkin, who made an aerial observation of an island of flat ice sandwiched around mountainous drifts. Two years later another Russian, Andrey Kapitsa, used seismic soundings to measure the thickness of the ice sheet around Vostok Station and hypothesized the existence of a subglacial lake. Still, few believed the lake could be liquid until the 1970s, when British scientists performing airborne ice-penetrating radar surveys of the plateau declared the unusual readings indicated the presence of liquid freshwater in Vostok’s vast basin. In 1991, a remote-sensing specialist from the United States directed the ERS-1 satellite’s high-frequency array at Vostok, confirming the British surveys.

More of a subterranean cavern than a lake, Vostok was divided into two deep basins by a ridge. The northern basin plunged thirteen thousand feet; the southern basin reached twice that depth. The ridge itself was situated in seven hundred feet of water and, as incredible as it seemed, harbored an island.

The weeks of summer flew by. To my father’s credit, his “monster mania” had resurrected tourism in the Great Glen for at least one more season, turning a potential economic disaster into a windfall. In fact, more tourists visited Loch Ness that summer than any other location in all of the United Kingdom or Europe.

But the “Hero of the Highlands” never apologized to me for his deeds or for the potential dangers associated with my upcoming deployment. And when the day finally came to say

goodbye, I refused to see him.

For the hundredth time that summer, I read my infant son his favorite book as I rocked him to sleep in his stroller by the ruins of Urquhart Castle. “In a great green room, tucked away in bed, is a little bunny. Goodnight room, goodnight moon… .”

Brandy and I spent that last hour holding hands. Then the taxi arrived and it was time to go. I absorbed one last memory of those green hills, the gray cliff face, and the foam spraying off of the tea-colored waters, and asked my Maker to bring me home again to my wife and child—just not in a box.

True climbed in the back of the cab and slapped me hard on the knee. “So? How soon do ye want to get shitfaced?”

“As soon as we get on the plane.”

Our flight out of Inverness was scheduled to depart at five o’clock on a Sunday evening, beginning the first leg of our journey—a twenty-seven-hour trip that included stops in Birmingham, Paris, Santiago, Puerto Montt, and finally Punta Arenas, Chile. After spending a day recouping in the southernmost city in South America, we would board a seaplane for King George Island, where a cargo plane would be waiting to fly us across the continent to Davis Base in East Antarctica. From there we’d have another day to adjust before flying out to the new bio-dome being erected over Lake Vostok.

Lying back in my first-class seat next to my snoring friend, I closed my eyes and attempted to organize my mental notes on our frozen destination.

At just over eight million square miles, Antarctica was bigger than both Australia and the United States combined, with ninety-seven percent of its land mass covered by an ice sheet that averaged two miles thick. The only continent not to possess an indigenous human population, Antarctica was divided into three distinct sections: its east and west regions and the peninsula.

A short flight for tourists arriving from Chile, the Antarctic Peninsula, nicknamed the “Banana Belt” by snarky scientists, included the South Orkney Islands and South Georgia. The peninsula’s climate was mild compared to the rest of the continent and was home to a myriad of summer wildlife that included seals, whales, birds, and the emperor penguin. The male emperor penguin was the only warm-blooded animal that remained in Antarctica throughout the winter months. Their job: to stay on land and keep their offspring’s egg warm by covering it with a flap of abdominal skin. While the females swam off to warmer waters, the males huddled in groups in sub-zero conditions, often going nine weeks or more without eating.

The Trench

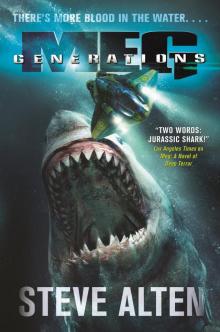

The Trench Generations

Generations The Mayan Resurrection

The Mayan Resurrection Vostok

Vostok Grim Reaper: End of Days

Grim Reaper: End of Days The Omega Project

The Omega Project Domain

Domain Meg

Meg MEG: Nightstalkers

MEG: Nightstalkers The Mayan Resurrection mp-2

The Mayan Resurrection mp-2 Goliath

Goliath Undisclosed

Undisclosed Dead Bait 2

Dead Bait 2 Loch, The

Loch, The The Loch

The Loch The Firehills

The Firehills Sharkman

Sharkman The MEG

The MEG Phobos

Phobos Meg_A Novel of Deep Terror

Meg_A Novel of Deep Terror Meg: Origins

Meg: Origins