- Home

- Steve Alten

The Firehills Page 4

The Firehills Read online

Page 4

Sam looked at her for a moment and then, with a tired smile, replied, “OK. Let’s explore. Lead the way.”

‡

Along the streets of the Old Town they came, in twos and threes, long overcoats trailing like black wings behind them. The ancient Sidhe, the Faery Folk, were gathering for the hunt.

Down on the seafront, the Lady Una sat on the wooden backrest of a bench near the boating lake, her booted feet placed demurely together on the seat. She had exchanged her black wedding dress for something more practical—a black leather motorbike jacket and a flowing, layered skirt of purple velvet. Her mane of black hair blew around her face in the cool breeze from the sea as she waited. Soon they came, fifteen or twenty of them, arriving in small groups, casually loitering around the bench in silence. When all were assembled, the Lady Una favored them with her characteristic smirk and jumped lightly from the bench. With a click-click of stiletto heels she paced off along the seafront, and her subjects followed behind.

‡

“Wow!” exclaimed Sam, “It’s heaving!”

They had left behind the relative quiet of High Street and plunged into the brightly colored chaos of holiday Hastings. The streets echoed to the rumble of powerful engines as bikers converged on the town. Over the years, the bikers had become a local tradition, and now hundreds of them paraded their machines along the promenade. The riders wove in and out of processions of buses pouring out their tourists. Here and there a knot of morris dancers in bells and ribbons pushed their way through the crowds, jingling and merry. The air was heavy with the smell of fried food and the salty tang of the sea. Sam found himself smiling, caught up, despite himself, in the holiday atmosphere.

“Come on!” shouted Charly. “This way.” She plunged off across the road, dodging in and out of the slow-moving motorbikes. Sam did his best to follow.

Charly stood for a moment on the opposite pavement, watching impatiently as Sam tried to copy her dash through the traffic. He was right. He did seem different. Distracted, as if he was listening to something no one else could hear. Looking around, she noticed a group of strangely clad figures clustered around a bench. Weirdos, she thought, taking in the nose rings and dyed hair. A few kids in her school dressed like that, when they could get away with it. Loners, mostly. Quiet misfits who wrote poetry and pretended to dabble in the occult. Charly, as a newly initiated Wiccan, had a very low opinion of dabblers.

She looked back and found that Sam had made it across the road and was gazing around in a vaguely bemused sort of way. “Come on, ” she groaned. “You’re so slow! ” With that, she set off along a road bearing a signpost to the strangely named Rock-a-Nore. As she turned to go, she noticed that the Goths around the bench were also on the move. For no apparent reason, this made her feel uneasy.

“What are these, then?” asked Sam, who had appeared at her side. He pointed to the buildings around them. They were among the tall black sheds she had seen from the car when they first arrived.

“They’re the net shops,” replied Charly.

“Right.” Sam nodded. “And that’ll be . . . where you buy nets?”

“Close, Einstein, but you’re guessing. They mostly sell fish from them now. But it used to be where the sailors stored things, fishing nets and stuff. They were only allowed so much space each, so they built upward.”

Sam’s eyes tracked up the face of the nearest net shop. Black-tarred planks loomed above him—three stories, each with a small door, the upper two opening out onto empty space. They seemed rather sinister, as if something were hidden behind the doors that shunned the daylight.

“Cheerful choice of color,” he muttered to himself.

“Come on,” said Charly once more and pulled him by the arm.

They made their way between the somber rows of huts, picking their way through piles of bright blue plastic net and coils of orange rope. Charly kept glancing behind them.

“You OK?” asked Sam.

“Mmmm,” replied Charly. “Sam . . .?”

“Yeah?”

“Do you know any Goths?”

“Goths?”

“Yes—you know, the vampire look? Black clothes, pale skin, bad taste in music?”

“I know what Goths are. We’ve got them at home. In fact, there were some hanging around our house when we set off yesterday. But no, I don’t know any Goths. Why?”

“No reason. Come on.”

She set off once more. Sam frowned at her back for a moment, then he called after her, “You are a strange girl, Charly!”

He hurried to catch up and found that they were on the beach. From the back of the net shops, the land dropped sharply to the sea. Here the fishing boats rested among rusting winches and old fish heads, as if a freak tide had left them stranded. They sat high on the beach, a row of compact, muscular vessels, their bright paintwork streaked with rust. Between them were scattered the hulks of ancient bulldozers, collapsed in the act of hauling the boats from the grasp of the sea.

“There’s no harbor,” explained Charly as they wandered between the ancient hulls, “so they use the bulldozers to winch the boats up onto the beach. Sweet, aren’t they?”

Sam looked unconvinced.

“My favorite’s called Young Flying Fish. ” She gestured over to a pug-nosed little craft hung with faded orange floats and topped off with a jaunty red and white life belt.

“Uh-oh.”

“What is it?”

Charly looked suddenly anxious. “You know when I asked you about Goths?”

“Yes?”

“Well, don’t look now, but there’s a big gang of them, heading this way.”

Sam turned. Striding through the old plastic fish crates came a group of dark figures led by a young woman in a leather jacket. She was stunning—delicate features, flawless skin, and a mane of dark hair that streamed out behind her as she walked. Heavy boots crunched on gravel as she and her companions made their way purposefully toward Sam and Charly.

“Look,” began Sam, “I don’t know what’s going on here, but I think we should get going. Charly?”

But Charly had already disappeared around the planked belly of one of the boats. Sam hurried to follow. Behind him, he heard the slither of stones as the blackclad youths broke into a run. Sam caught up with Charly at full tilt and grabbed her by the arm as he passed.

“Come on!” he bellowed. “Get us out of here!”

“This way!” Charly dodged left, into the maze of net shops, dragging Sam after her. Darting from side to side, she led him between the towering black sheds and out into the street. Looking back, Sam could see close to fifteen Goths thundering toward them. The girl was in the lead, a look of savage delight on her face.

“Ooops!” shouted Charly. “Trouble!”

Sam looked in the direction she indicated. Perhaps ten more Goths were headed their way from the town center. Charly grabbed Sam’s arm and pulled him in the opposite direction, out along Rock-a-Nore Road.

“Have you got any money?” she shouted.

“A bit. Why?”

“We’re going for a ride!”

Up ahead, Sam could see a narrow, sloping gully in the towering cliff face that formed the backdrop to the street. Nestled at the foot of this gully was what looked like the top half of a small blue-and-white streetcar. Sam was dragged through a gateway and up past a sign that said: East Hill Cliff Railway. Dodging in and out of a scattering of slowly moving tourists, Sam and Charly skidded to a halt at the end of a short line. In ones and twos, the people they had passed on their way in wandered up and joined the line behind them. And then the Goths appeared. They had slowed to a walk and took their place at the back of the line, unpleasantly close behind. Charly risked a glance back and found herself looking into the baleful gaze of the girl in the leather jacket. Their eyes locked, and Charly’s head began to spin. The girl smirked at her discomfort, and Charly felt a wave of anger sweep over her. She broke the eye contact and hissed at Sam, “Get your money read

y.”

Sam rooted around in his pocket and found enough change for the fare. They shuffled another place forward in the line. Ahead, Sam could see their transport—a small, squat vehicle, like a cable car. Unlike a cable car, however, it ran on rails that followed the steep slope cut into the cliff. The single carriage was rapidly filling up, and it looked as though only a handful of spaces were left. At last, they reached the ticket office. “Two half fares, please,” asked Sam.

“One of you will ’ave ter wait,” said the man behind the counter. “Only one space left.”

Charly went pale and glanced behind. A wave of malice washed over her again as she met the eyes of the darkhaired girl.

“But we’re together,” pleaded Sam. “Please?”

The man thought for a moment. “Oh, go on, then.” He smiled. “Don’t want ter stand in the way of young love.”

Sam went pink, but he handed over his money with relief. Grabbing Charly’s arm, he dragged her toward the carriage, and they piled inside. Squashed together in the sweaty throng of tourist bodies, they peered out through the glass as the Cliff Railway whisked them upward. Charly beamed down at the pale faces of the Goths and waved maliciously.

“Well,” breathed Sam at last. “What do think that was all about?”

“You’re asking me? I thought you might know.”

“Nope. We’ll have to ask Amergin.”

The carriage finished its smooth ascent, and the doors opened. With relief, Charly and Sam spilled out into the fresh air and made their way out onto the grassy summit of East Hill.

“We’d better make our way back down fast,” said Charly.

“The next carriage load is probably on its way up by now.”

“Do you think they’ll follow us?” asked Sam.

“How should I know?” Charly exclaimed in exasperation. “I don’t even know why they chased us in the first place. Although that girl . . .” her voice trailed off. They followed a path across the brow of the hill, heading for the steep, meandering steps that led back down toward the Old Town. Sam paused, looking down at the sprawl of buildings far below, the tiny boats hauled up onto the beach, the shadowy towers of the net shops, and farther along the shore, the multicolored bustle of the town. He felt a sudden breeze and turned around.

An unseen force was lashing the short grass of the hilltop. Here and there, cigarette butts and discarded tickets swirled around in frantic spirals. Suddenly—and Sam at first doubted his own eyes—suddenly they were surrounded by the Goths who had pursued them from the beach. Arranged in a loose semicircle, the black-clad figures stood in silence, as if newly sprung from trapdoors in the grass. Sam and Charly moved closer together. The girl in the leather jacket raised one hand, palm upward and fingers curled like claws. Once more the breeze sprang up, not swirling now but blowing steadily off the land and out to sea. Gradually, the breeze increased in strength, until Sam and Charly were buffeted by its force and had to lean forward into the gale to keep their balance. Sam glanced behind at the dizzying drop down to Rock-a-Nore Road. The black-haired girl abruptly clenched her fist and brought her elbow sharply down by her side. A savage gust smashed into Charly and Sam, drawing tears from their eyes and making them stagger backward. Charly felt one foot slip on the grassy edge of the cliff and clutched at Sam’s arm.

Sam glanced backward once more. “Charly,” he hissed, “you’re going to have to trust me now.”

Charly gave him an uncomprehending look, then shrieked in terror as he launched himself backward into the void, dragging her after him.

And then, with a familiar swirling sensation in her mind, Charly felt the wind beneath her wings and screamed once more, this time with the high, plaintive cry of a gull. Together, she and Sam wheeled on the warm updraft from the sea, white wings flexing and rowing the air. Sam turned and plunged, and Charly followed him, down to a concealed yard behind a seafront café. Again, she felt the swirling sensation of dislocation, and she was back in her human form.

“Don’t do that!” She laughed, exhilarated and relieved, slapping Sam on the arm.

“Sorry.” He grinned back. “You OK?”

Charly nodded.

“Come on, then. We’ve got a lunch date.”

‡‡

They stepped out through a narrow passageway into the crowded streets and found themselves close to the Mermaid Restaurant. Megan and Amergin were already seated at a white plastic table, four steaming plates of fish and chips in front of them. With a wave, Charly and Sam made their way through the crowd and took their seats.

“Mum,” began Charly, tucking into a chip, “you will never guess what just happened to us—are you two OK?”

Charly sensed a certain coldness in the air.

“Oh, yes,” replied Megan, “we’ve had a great time. We’ve been on the choo-choo train, haven’t we?” She favored Amergin with a sour look.

“We can go to the museum this afternoon,” said Amergin with the look of a man in the doghouse.

“Anyway, go on,” continued Megan. “What happened?”

“We got chased by weirdos! We had to jump off the cliff!”

Megan looked shocked.

“It’s OK. Sam turned us into gulls.”

Megan looked only slightly less horrified. “Who was chasing you?” she demanded.

“Weirdos! Dressed in black, you know—Goths. There was this girl, and she made the wind start blowing. Nearly blew us off the cliff— ”

“The wind?” snapped Amergin, suddenly alert. “You say she made the wind blow?”

“That’s right,” agreed Sam. “She lifted her hand up and the wind started blowing.”

“Describe these . . . these Goths.”

“Dressed all in black, pale faces, long hair, tall, and thin—Goths. You know.” Charly shrugged.

“Ah,” sighed Amergin. “This is grievous.”

“Oh, dear,” whispered Charly to Sam, “He’s off again.”

“What is it, Amergin?” asked Sam.

“There is one race, my friend,” began Amergin, “who has the power to command the wind. The Hosts of the Air. They are known by some as the Faery Folk, by others—”

“Fairies!” spluttered Sam, almost choking on a chip.

“These weren’t fairies. No wings, for a start.”

Amergin chose to ignore him. “They are an ancient race, cold and cruel. The Sidhe they were once, in ancient Ireland, and before that, the Tuatha de Danaan.”

“I know that name,” said Charly thoughtfully. “You’ve mentioned them before.”

“Aye, child, for my path and theirs have crossed.”

Amergin fell silent, lost in thought.

“There’s a story coming,” Sam whispered to Charly.

“Get comfortable.” She kicked him under the table.

“Long ago,” began Amergin, “as I have told, I came to the land you know as Ireland with my people, the Sons of Mil. And we saw that the land was fair and desired it. But a race dwelled there before us—the Children of the Goddess Dana, the Tuatha de Danaan.”

“So what did you do?” asked Charly.

“We took their land from them,” Amergin replied simply. “We slew them and took their land from them. And those we did not slay, we drove underground. Into the Hollow Hills.”

“Where’s that?” asked Sam.

“The Hollow Hills are . . .” Amergin trailed off.

“Here . . . and not here.”

“Right. That’s cleared that up.”

“Sam!” hissed Charly.

“The Hollow Hills,” continued the wizard, glaring at Sam, “are a realm separate from ours, touching upon it in some places but in others far removed. There are gates, doorways into the hills, but once a man enters, he can never know where—or when—he will emerge.”

“So,” began Sam, “these fairies—the Sidhe—you and your tribe took their land from them, right?”

Amergin nodded.

“And you killed most of them and

drove the rest underground somewhere?”

Amergin nodded again, looking unhappy.

“And you’re the last survivor of the Milesians, the sons of Mil, yes?”

Another nod.

“So why are they chasing Charly and me? If they’ve got an axe to grind with anyone, shouldn’t it be with you?”

“It may be,” replied the wizard thoughtfully, “that they are trying to get to me through you.”

“Well,” said Charly, “could you arrange to have them chase you next time?”

“I think,” replied Amergin, ‘”that we should all stay very close together for a while.”

‡

Their meal finished, they made their way back through the crowded streets toward the town center. Charly felt insecure, even in the presence of her mother and Amergin. The pavements seemed crammed with hostile faces.

Meandering through the streets of the Old Town, peering into the windows of old bookshops, they eventually spilled out onto the seafront once more, with its amusement arcades and souvenir shops. Caught up in the crowds, they walked on, under the foot of West Hill.

Above them loomed the ruins of the castle, where the festival would be held. It seemed to cling precariously to the rock, jagged and broken. Finally, they came to the newer part of town.

“I know,” said Megan, pointing across the road, “let’s go to the pier.”

“I thought,” replied Amergin rather huffily, “that you didn’t approve of such things.”

“It’s industrial archaeology,” said Megan, grinning, “a triumph of Victorian architecture.”

They found a pedestrian crossing and shuffled with the crowd across the busy seafront. The pier launched itself out to sea from a wide plaza, ringed by stalls selling ice cream and seafood and dotted here and there with jugglers. Passing through a narrow gate, they found themselves out over the sea. The restless motion of the waves was visible through cracks in the old planks beneath their feet. They strolled on, with the sea breeze in their faces, past fortune-tellers and hot dog stands, past the old ballroom, to the farthest end of the pier. Here they stopped and leaned against the railings in a comfortable silence, gazing out to sea.

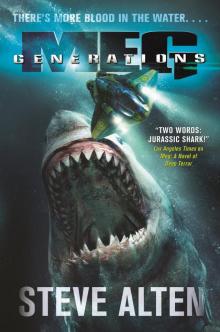

The Trench

The Trench Generations

Generations The Mayan Resurrection

The Mayan Resurrection Vostok

Vostok Grim Reaper: End of Days

Grim Reaper: End of Days The Omega Project

The Omega Project Domain

Domain Meg

Meg MEG: Nightstalkers

MEG: Nightstalkers The Mayan Resurrection mp-2

The Mayan Resurrection mp-2 Goliath

Goliath Undisclosed

Undisclosed Dead Bait 2

Dead Bait 2 Loch, The

Loch, The The Loch

The Loch The Firehills

The Firehills Sharkman

Sharkman The MEG

The MEG Phobos

Phobos Meg_A Novel of Deep Terror

Meg_A Novel of Deep Terror Meg: Origins

Meg: Origins