- Home

- Steve Alten

Dead Bait 2 Page 2

Dead Bait 2 Read online

Page 2

Bachelor parties, birthday parties, weddings, bar mitzvahs; every one of them and more had boarded the Glory Hound. Once, an old Pole from Danvers wheeled himself onto the boat, alone, wheezing like a broken vacuum cleaner, half-crazy with cancer meds and marijuana, raving about hunting for Moby Dick. Fontaine called an old lawyer client and prepared the necessary paperwork in case the Polak croaked on the boat. They trolled for three days and caught nothing but colds and sunburns. But he let the man sit in the chair and hold the pole. He reeled it like a madman intermittently, coughing and hacking. Later the Polak, Wyrzevski was his name, altered his will to include Fontaine. He left him a lamp, the base of which was a hand-painted, pipe-smoking sailor. It used to sit on Fontaine’s bed stand, gnome-like and enigmatic with its smile, driving Galadriel’s anger with its very presence.

Hidden now, the plaster sailor slept beneath a sweater and old lo mein boxes.

Yet among the complexities of captain Fontaine, his greatest paradox, perhaps greater than his ability to be completely mad yet run his business with admirable efficiency, was the legendary status he had reached as a navigator despite the most profound shortcoming imaginable for a man of the sea.

Summer people, in the hot months that smelt more like dogwood and hycinthias than salt and wind, crammed the docks with sun fish and schooners and speedboats and jet-skis and other idle contraptions of the rich. Anyone determined to reach open ocean had to navigate the Swatch, a narrow inlet that was not quite a bay. Some spots were only a foot or so deep during low tide and the passage could get choppy and dark at a moment’s notice, tips of submerged rocks peering out like periscopes of enemy submarines.

No one could navigate the Swatch like Fontaine. He bobbed and weaved around the straight better than any other sailor on the Cape. It was not uncommon to find a train of younger captains hauling out behind the Glory Hound, mirroring his path. Sometimes they’d delay their trips if Fontaine ran late or strand a late patron on the docks clutching a six pack because the day was particularly choppy and they didn’t have enough confidence to shoot through the Swatch without Fontaine’s lead. Word of the phenomenon stretched to all over ports from Falmouth to Provincetown and as far east as New Bedford.

Unknown to Fontaine, this innate sense of direction was his only inheritance, besides the boat, from his water-logged father. In his infancy Fontaine had been quite attached to the buoyant, adventuresome man who’d sired him. When he was taken on deck by his mother that final time, along with their family and many of the other captains, he’d stared silently out with the same panoramic stare, all the way to the spot where his father had been dragged off his own boat in the clutches of a spring squall. After that the route was forever burned into his memory. When he doodled he’d draw it in all its variation according to wind and moon and stars without any knowledge of what he was really doing, scrawling maps worth thousands of dollars across yesterday’s funny pages, loops and hooks and zigzags.

But the great shortcoming was that Fontaine never caught any fish.

He used to. Shortly after high school when he’d put the boat in the water for the first time in sixteen years he reeled in stripers and albacore and makos and every other slippery beast in the sea. They met their end and bled on the point of his gaff. Then he’d married Galadriel and the children followed. The ocean lost its purpose as a companion for him and he took to hooking rich people instead. Much to the other Captain’s annoyance and shame, this worked beyond his wildest dreams. Fontaine believed himself the happiest man on earth.

But it had been Galadriel who’d wrung the purpose out of Fontaine. Now he was left to continue his profession hollowly, like a priest who’d lost his faith administering communion.

Alone at the bar in Hooters, surrounded by wood paneling and satellite sports channels, Captain Fontaine smirked into his beer.

“Captain?” Candy said.

Like all the girls she wore a tight, garish outfit of white and orange, face painted into a mask of desire. Their chatter and bright colors reminded Fontaine of parrots. All of them called him Captain, fondly, as did everyone, a phenomenon which created a decidedly unfounded (especially in his delicate condition) air of authority about him, leading people to consult him on all types of matters, from marriage counseling to pet care, in which he had no business giving advice on.

Fontaine was hardly aware of their reverence anyway. In his mind he merely chose to drink his beer and chat amiably with anyone who cared to, locals or game, and slowly stew in the juices of the madness that kept him sleeping in that queen-size junkyard that smelled, if he tried hard enough, like the ghost of Galadriel’s body, undercut with tinges of sadness, solitude, sweat, and soy sauce.

“Captain?” Candy repeated. “That man sent this over here.”

She slid him a Heineken. Fontaine smiled, straight rows of white teeth glistening. Candy returned her own smile, delicate and falsely bashful and sashayed away into the kitchen.

Fontaine raised his head. At the end of the dark, varnished bar sat a smartly dressed man of about forty-five, with a leisurely tan as dark as his own but owning none of the same rugged quality. He was handsome in a dangerous way and several of the waitresses fawned over him, brewing private dreams of being whisked away to live on movie sets or in southern mansions. The most peculiar thing was his fingers. They glittered with rings of all types: silver, gold, platinum, some bearing dark stones, others simple bands. They clinked on his bottle when he drank, and when he did he drank deep, pulling on his beer until it was half gone, feigning a sheepish grin as if in wonder at his voracious thirst.

“He’s rich,” Candy mouthed conspiratorially. She was new and had yet to realize that everyone on the Cape was either rich or depressed that they weren’t. Nothing about this man exuded depression.

Fontaine sent a fresh beer ahead of him toward that end of the bar, then trailed it slowly, pausing to chat with other regulars, all men, all slightly more pathetic than him in some way, if not only for the way they fondled each waitress with their eyes, breaching every curve, while he kept staring in his strange way past them, at everything all at once. That was part of the reason why the girls liked him so much and helped him field his quarry.

“El Capitan!” said the man, raising his glass, sloshing beer out of it. “You didn’t need to send this.”

Fontaine shrugged, sat next to the man. “Hear you want to catch some fish,” Fontaine added, needing none of the silly banter he usually engaged in about the Red Sox or the stock market, which he only pretended to understand. He was good with people in a direct way, impersonal and efficient without being cold.

“Sharks,” the man said blankly, expecting some response from Fontaine, something of incredulity or impressiveness. Fontaine had seen a million and five sharks in his lifetime. “Heard you get mostly blues out here,” he added.

“Sure, we’d probably get blues,” Fontaine said, avoiding, as always, a direct lie. “We could get makos too and some threshers, but blues the most. Can’t tell, you never know what’s down there.”

The man smiled and spread his hands at Fontaine, rings glittering. Some fingers were three or four rings deep. “Thing is, I have a damn boat! I need a Captain! I have a yacht and some pansy ass, fruit wearing, short-shorts, putts it up and down the canal for me. Big shit!”

And he ordered shots of tequila, which they drank together. Fontaine detested tequila, but trolling for dollars forced him to drink all manner of alcohol that he detested and they blended into one fiery liquid that he sucked down without joy or relish, but with the resolve of workmanship. After an hour, he’d worked himself into a fervent drunkenness, along with the man, who had bought all the tequila and Coronas in the bar, as well as, supposedly, the southeasterly quarter of Cuttyhunk.

“Don’t worry. I’m leaving it just the way it is. It’s just part of the collection,” the man said. He wiggled the rings in Fontaine’s face. “Bet you’re wondering what these are all about,” he said.

Befor

e Fontaine had briefly wondered, but now he only watched the room spin and buzz. The man chuckled to himself and made no attempt to explain the comment.

Fontaine raised his eyebrows.

“I wonder too sometimes,” the man said cryptically. “Must be nice, you know, simple, on the ocean, you against the fish.”

“Lishen,” Fontaine slurred, then recovered himself. “Once, this bachelor party books a trip. Ten men, none of them fishing, just getting blitzed and puking over the side of the boat and sleeping on the deck. That night, the dads and uncles and cousins all pass out. I cut through the cabin to get to the head. Two shapes are moving around under the blankets like tomcats in a potato sack. I say ‘holy shit’ just out of basic nature. Then the groom-to-be and the best man poke their heads out.

“Please mister, don’t tell anyone” he begs. I close the door of the head behind me.”

“You tell the wife?”

Fontaine paused dramatically out of instinct, unaware of what a good storyteller he was.

“She met them at the docks. Asked what they caught. I told her only thing we managed to get were a couple of rainbow trout.”

The man guffawed, holding his belly.

“Ain’t what you think out there,” Fontaine said honestly.

“You take cash?” the man asked.

Fontaine thought about what he’d like to be paid in. He’d like to be paid in moments with his wife. He wished this man could take out his wallet and withdraw kisses and movies on the couch together like dollar bills from its folds.

“Say there,” a man sidled up to the two of them. A handlebar moustache hung under his nose. He wore a denim jacket and was roughly the size and shape of a keg of beer.

“Tolliver,” Fontaine acknowledged. Tolliver was, in fact, the anti-Fontaine. His patrons caught loads of fish, hauled them in by the bucketful. He ate smoked striper for breakfast, codfish cakes for lunch and mako steaks for dinner. But Tolliver failed to attract the money which Fontaine so easily angled. He couldn’t understand this dynamic and pored over it nightly as he watched Fontaine at the bar, sucking in the clients like a baleen whale. Tolliver would never figure that out while he pitched a guarantee of slimy, bloody fish to his clients, Fontaine’s mere demeanor pitched the carefree, adventurous lifestyle each man yearned for secretly since boyhood.

“So, you gonna take this fellow here shark fishing but you ain’t going to tell him ‘bout the tourney?” Tolliver asked, leering.

In actuality, Fontaine himself had forgotten about the tournament long ago. Twenty years it had been going on. In the early days, before Galadriel, he fished it and put up respectable poundage. Once he placed second.

“Tournament?” the rich guy asked.

“Oak Bluffs Monster Shark Tourney,” Tolliver said slowly, emphasizing the word monster. “On ESPN and everything, ‘bout two-hundred-fifty boats.” The squat man narrowed his eyes. Fontaine, as expected, merely sipped his beer and shrugged, but the billionaire was hooked.

“Three day trip,” Fontaine said blithely, swirling the dregs of his beer, “Little more expensive.”

Tolliver had already debated to himself whether to seduce the rich guy to fish on his own boat or to let Fontaine suffer such crushing embarrassment that it would surely ruin his business on the Cape. Banking that Fontaine would trap himself, he staved off his greed and settled for the latter. Tolliver watched with relish as Fontaine goaded the man into booking the trip with careless affectations, nods of the heads, shrugs, and throwaway mentions of fish the size of French armoires. He’d seen this dance before, from his regular booth in the corner behind a pile of chicken bones and jealousy.

“Prize is a 31’ Fountain with twin 225 horsepower Mercury outboards plus the trailer,” Tolliver chimed, salivating, “Gear like that’ll run a man a hundred and a half, likely.”

“My membership might’ve run out,” Fontaine said into his glass. Competitors needed to belong to the Boston Big Game Fishing Club, the group that organized the tournament. “Actually, it did.”

Tolliver thought fast. “Well, if the boy here wants a shark in July he ought to fish the tourney. Shame not to. Tell you what, I’ll let you use mine.”

Fontaine raised his eyebrows, seemingly about to protest, but suddenly winked at the rich man. “Well, I guess that’s all up to the big guy.”

“You bet your ass it is,” the man replied grinning. He ordered another round of Buds, since they’d drunk all the Heinekens and Coronas. Asia, the black girl, ran up the street to buy more Cuervo at the man’s behest, a hundred dollar bill in her fist. Fontaine sighed, letting the booze carry his mind away to a place that was not the immediate present, filling up his consciousness with the fog that carried him through each day.

At some time during the night he left the bar in a stupor, strolling down the empty streets, gazing at the replica street lamps and wheelbarrows on the lawns and thinking of nothing at all, for nothing seemed different than any other trip he had booked. The captain had not owned his own car in over a decade, and so walked everywhere, savoring the sound of his feet against the ground, imagining the hot center of the earth miles below his feet. The image of Galadriel chugging away in the minivan crossed his mind and for the briefest moment his eyes watered before the madness evaporated his tears.

Somehow, before he knew it, he was in his garbage heap of a bed. Days passed without distinction as he rose and fell with the sun, eating burgers and Buffalo wings. He polished and primed the boat, ground chum, froze mackerel, lounged in the air-conditioned cockpit of his boat while men with sweaters tied around their shoulders drank gin and tonics and held the fishing equipment gingerly, like a gun with the safety off. The wet spring began to dry out, the grass turned brown, and suddenly fireworks were going off over Buzzard’s Bay. Galadriel had not returned, and Fontaine no longer answered his mother’s phone calls about the children. When the man called to confirm the trip, speaking in brisk phrases like punches, Fontaine vaguely recalled the encounter, as his madness was in such an advanced state. Of course, it was posted in his date book in scratchy, rear-leaning scrawl. There was no denying the trip was a reality. On the appointed day he readied his boat, unprepared for anything spectacular.

All mornings are gray. Eventually they may ascend into a pink, slivery, blossoming skylight, ever shading into the electric-blue of true daylight, but they are all born equal. On July seventeenth the man arrived in a gigantic SUV called a Minotaur that Fontaine had never even heard of. The rich man stumbled into the gray of three-thirty a.m. wearing wrinkled shorts and a tattered baseball cap, a small bag slung over his arm and a large cooler in his fist.

“Which one’s the boat?” the man squinted at the docks, listening to the other boats knock against them. Fontaine pointed out the Glory Hound.

For seasoned fishermen, shark fishing is a kind of cakewalk. The plan was to coast along the northeast end of Martha’s Vineyard, dripping chum in crooked, oily streaks for miles, dragging chunks of mackerel and garrulous flocks of gulls behind them. Fontaine explained it all before to the man over the phone, after he’d set up their entrance fee and mooring and check-in, so that they’d get to begin fishing directly instead of motoring all the way in to Oak Bluffs and back out again before dawn. They loaded clothes, beer, and sandwich meat onto the boat. Fontaine brought some tequila even though he liked to keep hard liquor out of the picture. Too unpredictable, but in some cases called for.

“Which ones can we eat? The man asked, easing into the fighting chair.

“Any but the blues, really,” Fontaine said. “In a bind, though, I guess you’d eat any of them.”

“Make’s Mother Nature happy to eat what you kill,” the man said, hands behind his head, eyes invisible beneath his sunglasses. “Some kind of Indian mumbo-jumbo-balance bullshit, right?”

Fontaine’s newest customer was unaware that running a vessel like the Glory Hound usually required two people. Steering against the winds and tides and wills of the elements, cutting c

hum, hacking chunk bait, pulling and letting lines, all took valuable attention. Fontaine always managed everything himself. When his catch dropped off he’d fired Arnold, his old Swedish deck hand. He realized that this person was still just the rich guy in his head. He’d paid with a sharp-looking stack of hundreds that Fontaine quietly locked away in a place no one else on planet earth knew about.

“I just realized I don’t know your name.”

“Caldwell,” Caldwell said, jerking a thumb at his chest, not knowing Fontaine’s name himself but too proud to ask. “Now start that fucking engine,” he said in a very friendly way. The engines rumbled, the briny water gurgled beneath them, and they churned their way toward the horizon, well on its way to not being gray anymore.

Caldwell spent the first six hours sleeping violently in the cabin, making thumps and thwacks and bumps and grunts against the door, sounding much like a blue or a thresher galumphing beneath the hull. Fontaine didn’t care. He was alone, passing the time as he always did, looking forward to the night, when he could gaze at the coast of the Vineyard, invisible to the untrained eye, like the buried spine of some ancient dinosaur. The lights would be like stars sunken into the ocean, the eyes of mermaids gazing out Atlantis’s basement window.

The day was sprinkled with wet, salty showers.

The Trench

The Trench Generations

Generations The Mayan Resurrection

The Mayan Resurrection Vostok

Vostok Grim Reaper: End of Days

Grim Reaper: End of Days The Omega Project

The Omega Project Domain

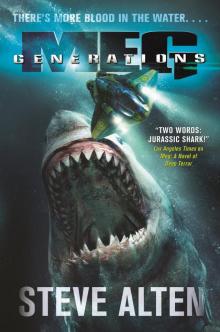

Domain Meg

Meg MEG: Nightstalkers

MEG: Nightstalkers The Mayan Resurrection mp-2

The Mayan Resurrection mp-2 Goliath

Goliath Undisclosed

Undisclosed Dead Bait 2

Dead Bait 2 Loch, The

Loch, The The Loch

The Loch The Firehills

The Firehills Sharkman

Sharkman The MEG

The MEG Phobos

Phobos Meg_A Novel of Deep Terror

Meg_A Novel of Deep Terror Meg: Origins

Meg: Origins