- Home

- Steve Alten

Dead Bait 2 Page 13

Dead Bait 2 Read online

Page 13

A flashlght beam pinned him to the spot. “Don’t move!” said a low voice, but he unclenched when he realized it was Lorna.

While he ate the tunafish sandwich, she tried to tell him why. “When a farmer grows corn, he must labor and give it his blood and sweat, and in the end it feeds his family and he’ll plant more corn. He serves the corn. It’s no different here.

“When all the fish died, the island went hungry. But we were born here and weren’t meant to leave. They came up from the depths some years ago and they were something new, out of something very old. Doc Kinchloe called them isopods—living fossils. We called them a miracle.”

Their cycle was broken too, for while they fed on all sorts of deep sea life down there in the dark, they turned into cannibals when they came to the surface to spawn and devoured their own eggs, if they were not separated and farmed. So the island learned to live off the new bounty from the sea, but they had other troubles.

Generations of inbreeding had led to nervous conditions and defects, like the deafness and palsies and seizures. The isopods were scavengers that ate, among other things, tons of medical and industrial waste dumped in their benthic feeding grounds. But something they ate or something they always were or the divine hand of the Creator, had made them just a little bit human.

“That’s right,” said Aunt Meg. Her kerchief-bound head peeked over the wall of the treehouse. “I thought I’d find you kids out here.”

“You can talk!” Joe said. “You were faking it!”

“No, dear,” she said, “I’m healed.” She lifted her hair and showed him a fresh incision just behind her ear. Something inside it squirmed. She flinched in pain, but her smile at hearing and speaking again more than made up for it. “That’s the miracle. If God meant for us to live somewhere else, we would’ve been born there. He provided for us. The catch doesn’t just feed us, Joe. If we look after them and give them a soft harbor, they can heal us all.”

Joe looked to Lorna, who lifted her shirt. He’d seen more of her than anyone already, but the sight of her breasts was not what he’d hoped. A livid pink bump on her collarbone, the size of a baby’s fist, trembled when she touched it. “I was born with a bad heart. They put them in me… or I would’ve died a long time ago.” With her slender body between Joe and her mother, she slipped something into his hands and flared her nostrils at him until he put it away.

Joe looked from one to the other, his mind reeling. It took him a little while to form a coherent question. “But if this is all so normal and natural, where’s my Dad? Why is he hiding in the hatchery?”

Aunt Meg looked shamefaced for the first time. “I’m sorry about that, but you couldn’t know about him, if we didn’t know about you. Your father has a very important job. After all, he was the one who showed us how to use them.”

Aunt Meg stepped aside and someone else came out of the dark behind the flashlight. Long, rangy arms reached in and grabbed Joe by the lapels of his jacket and jerked him out of the treehouse.

“We didn’t want to keep him a secret from you, Joe, but you have to understand. He never really cared about family or about having a home. He hurt people here and tried to leave, but he had an accident and everything turned out for the best. He’s… different, now. Don’t expect too much…”

Joe kicked and screamed in his father’s arms as the big man carried him out of the canyon. He knocked the hat off his head and all the fight went out of him. Joe’s Dad was still Joe’s dad up to his eyebrows, but his skull was a yawning, broken dome, filled to overflowing with something else.

An articulated shell, purple black with mottled pink spots, squeezed into the gap. It looked like a cross between a giant woodlouse and one of those prehistoric crab-creatures, a trilobite. Jointed legs with vicious claws scuttled and twitched against its underbelly, and its stubby lobster tail coiled and uncoiled out of the gaping wound, but its head was tucked in behind the mask of Sam Myrick’s face.

Like a hermit crab in a deluxe human shell, the thing looked out of Dad’s eyes at Joe as it carried him down to the docks, but was it really making his father’s lips mouth his son’s name and say, I’m sorry?

They went down to the cove, where the whole village waited. The women were out on the water in three long rowboats. They had dragged an enormous net across the width of the cove and now they sat at their oars and drummed on big tubs, a slow, pulsing dirge that reverberated through the water and the shore. The large fishing boat lay anchored in the center of the cove, with all its engines and motors shut off, a white island in the blackness.

The three dozen fit men and boys of the island raised a cheer and ran to their own rowboats when Joe’s father came down onto the dock bearing his son like a trophy. The Clijsters, Rowbottoms, Blys, Smoodys and Myricks stood aside as Sam Myrick passed among them. Uncle Tab punched Joe in the arm and dropped a crusty lifejacket around his neck, but looked away and shook off his clutching arm.

The full moon peered over the headland, paving the black wasteland of ocean with a road of liquid fairy gold. No motors churned the water. The wavelets that slapped the sides of the rowboats were hushed and drained of force. The swollen tide was like an upwelling of infected, toxic effluvia from the depths, like the last, sour breath from diseased lungs: stifling and sickeningly warm, spiced with the narcotic reek of benthic decay.

Joe’s father set him down in the prow of the first boat. None of the other eight young men in the boat looked glad to see him, except for Angus Smoody, who sat amidships and grinned at Joe. His arm looked no worse for having been crushed this morning, but for a jerking and twitching of each finger on his hand, one at a time, as if something were testing them. Bandages under his faded Blue Oyster Cult T-shirt wrapped his arm and chest, and covered a ring of squirming bulges around his shoulder and down his trembling arm.

He pointed at Joe once, then took up his oar. Joe had no oar. He turned around to look down into the water.

The cove rolled and sloshed in long slow movements, like a bathtub stirred by a vast, submerged body. Out beyond the point, the ocean was rent by frenzied slashing waves. The women raised a cheer and increased the tempo of their drumming.

The water was redder than blood, clotted with clumps of eggs like unripe grapes and chopped by sleek lilac shapes. Broad, armored backs broke the surface and grated the keels of the rowboats. The smallest of them was over three feet long and their jointed shells were crowned with spines like harpoons. Their blunt heads were fused with their thoraxes with two pairs of segmented antennae and four dull gray, sightless eyes. Jutting mandibles with sawtoothed ridges snapped out of mouths like garbage disposals. Recalling how few of the local fishermen had all their fingers, Joe drew back from the water.

A stiff arm shoved him over the gunwale and Angus’s hot, whiskey-laced breath washed down his neck. “They come up from a mile down to lay their eggs and eat each other, little boy. They’ll strip you to the bone faster than you can scream. And those are just the girls.”

“Get off me, fucker or I’ll hit you again.” Joe looked from the redheaded boy’s ruddy pug-face to the slack, vacant mask of his Dad. Mayor Smoody sat in the stern of the second boat, passing around a jug.

Angus laughed. “He won’t save you.” His injured arm jerked and dug its fingers into Joe’s shoulder. “If somebody falls in, they come running and stay to feed and the catch is fat enough to last all year, isn’t that so? What d’you say, boys?”

The men kept rowing, but they stared right through Angus at Joe. The moonlight made waxy masks of their faces, but none of them said a word.

On the crow’s nest of the hatchery ship, old Ichabod blew a bosun’s whistle. The mouth of the cove turned to foam. Sam Myrick stood up and silently pointed and the boats turned into the thick of the foaming water.

“Row, boys, row!” Mayor Smoody croaked. The bow dipped and rose, then began to bump and jerk as if they rode over a bed of boulders.

Joe leaned back close to his father, but he fe

ll off the bench with the rocking of the boat. Angus laughed. The floor of the boat was filled with harpoons and spearguns. Joe grabbed a heavy iron rod, but the barbs cut into his soft hand and he dropped it.

The males were bigger. Hundreds of humped backs came pouring into the shallow cove. Their dorsal spines parted the water like shark fins. The red water turned to pink foam with clouds of creamy white discharge from the second wave of isopods. They raged and tore at each other as they fertilized the egg masses, then swept across the cove to attack the females trapped in the nets the women had set up across the harbor.

The nets were heavy gauge woven stainless steel. The smaller females streaked through its loose grip into the open sea, but the larger isopod cows were ensnared and easy prey for their mates.

The men towed the net across the mouth of the cove to trap the spawning isopods. Half dropped their oars and took up the drawstrings of the net, pulling it taut and closing the enormous mouth like a purse around the swarm.

Joe sat with his hands clamped to the bench, but he was ripped free with no effort at all by Angus’s broken arm. “Clumsy Myrick, just like your dumb dad,” Angus said. “You’re gonna fall in.”

Joe grabbed a speargun and swung it at Angus, who trapped the shaft under his arm. Joe’s hand jerked it backwards, pulling the trigger. The spear whooshed out from under Angus’s arm and passed over the heads of the other boys.

In the next boat, Mayor Smoody reared backwards with one hand resting on the thin spear where it sprouted from his solar plexus, and fell overboard.

The red water closed over him and came alive with teeth. A lifesaver was tossed. A man reached down, but something pulled him overboard, and the lifesaver was shredded before anyone noticed that Angus had thrown Joe out of the boat.

The cold, viscous soup smothered him, like wet plaster or half-hardened gelatin. Joe kicked for the surface. Something in his jacket pocket fizzed and flooded his nose and mouth with noxious bubbles. The packet Lorna gave him reacted violently with the water. When his head broke the surface, he was stained a bright yellow. Heart pounding the back of his throat, he reached out for the boat, gagging, “Dad, save me!”

The boat had capsized.

Thrashing bodies all around him screamed for someone to save them. The other two rowboats came abreast and threw harpoons and lifesavers, but the second boat overturned from wounded men trying to climb into it all at once.

Hands shoved him under the water as someone tried to climb on top of him. He fought them, but the arm he grabbed came away in his hand.

The water in his ears roared with the sound of motors, but it was the chattering mandibles of the isopods feasting all around him. His hands slid without purchase on the slimy hull of the capsized rowboat.

Something under him lifted him up by the seat of his sodden jeans. He curled up into a ball, no fight left in him. He was shoved up out of the water and thrown over the keel of the rowboat, and there he lay, clinging to the cold wet hull like a newborn to its mother while all the men of Quiet Island were slaughtered.

He saw only clasping hands and rolling eyes, peering up out of the red chowder. The third boat, filled with old and crippled men, was swamped by a male isopod the size of a VW Beetle with dozens of frenzied females boring into its bleeding exoskeleton.

When there were no more men in the water, the surges gradually subsided. The water around him was a thick, steaming stew of gutted isopods and human limbs. The rowboat turned and slowly, jerkily drifted to shore. Joe looked up and saw Lorna and Aunt Meg and Grandma Amelia on the sand, dragging the rowboat in by its dragging painter.

When he slipped off the boat in the shallows, he staggered, but Lorna came down and caught him. She led him out of the water, but pulled on him when he tried to sink to the rocky shore to rest.

The women were waiting for the conclusion of the festival. All the young ladies of childbearing age stood in a line, their somber eyes glazed with instinctual need. This, too, was a vital part of the catch, and the life of Quiet Island.

They waited with their eyedroppers and buckets for the men to come home.

LOST IN TIME

Steve Alten

The store is a converted garage, located on a track of land close to the beach on the outskirts of St. Petersburg, Florida. Hardwood display cases are stacked against the walls. Folding tables, covered in dingy-white cloth, divide the main room into three sections. On one table, a collection of Megalodon shark teeth, lead-gray and sharp, sit upright in plastic stands like six-inch stalagmites. Ammonite and trilobites share another table with jagged chunks of quartz crystal, the colored stones glittering beneath the store’s bare light bulbs. Mammal bones and fossils from ancient Mastodons and ground sloths, camels and bison are displayed on the last table, along with bronze sculptures and bottles from the sixteenth century. Two racks of t-shirts and some original paintings complete the inventory.

Brian Evensen takes a deep breath, inhaling the musty scent of fossils and artifacts. The fifty-two year old divorcee registers butterflies in his gut as he wipes dust from an oak display case.

They’re late. Par for the course…

He rubs the display case glass with a Windex-soaked paper towel, then lovingly rearranges the Indian artifacts he has spent more than forty years collecting from local rivers and construction sites.

The deep throttle of the Harley-Davidson bellows in the distance. Brian continues cleaning, his heart racing. He listens as the motorcycle turns into the gravel drive and skids to a halt beneath the neon-blue “LOST IN TIME” sign.

Bells jingle. A gust of wind carries a whiff of cheap perfume and tobacco. Brian inhales his ex-wife’s scent, then turns to face her. “Hello, Dot. You look good. Maybe a little tired.”

“We’ve been on the road a lot.” She looks him up and down. “You lost weight.”

“Prison’ll do that for you. Where’s the asshole?”

“Wade’s outside and I doubt you’d have the balls to say that to his face.” She strolls around the store, feigning interest. “When do you re-open?”

“Next week.”

“Same ol’ same old.” She fingers a quartz rock, then looks up at the five-and-a-half-foot long sea creature mounted above her head. “Jesus, what the hell is that?”

Brian smiles. “It’s a viper fish. Chauliodus sloani. Very rare.”

“It’s hideous.”

“Yep. It’s a deep-sea fish that migrates vertically up from the depths at night to feed. Most specimens are only a foot or two in length, this particular sub-species grows to almost six-feet.”

“Its mouth reminds me of that monster in those Alien movies.”

Brian positions a small step-ladder against the wall. He climbs up, unhooks the mounted trophy from the wall, then descends, laying the creature upon a tabletop for closer inspection.

Dot tucks strands of oily black hair behind her ears as she bends to examine the gruesome predator.

The body resembles that of a six-foot eel, its scales colored an iridescent dark silver-blue, its flank blotched in brown and yellow hexagons that reveal small light-producing organs. The viper’s head contains large, bulbous, silver-rimmed eyes.

The most frightening feature is the fish’s mouth. Hyperextended open as if unhinged, it contains needle-sharp, dagger-like fangs that are so large they cannot fit inside the creature’s orifice while closed. Instead, they curve outward, running outside of the jaw. Two enormous lower fangs are so large, they would pierce the fish’s glowing silver eyes should the mouth ever close.

Dot touches the point of a fang, drawing blood. “Ouch. You say these things stay deep?”

“Except at night. Wanna see something cool?” Brian points to a long antennae-like organ trailing back along the body. “This is a light organ. The viper fish dangles it in front of its open jaws, flashing it on and off to attract prey. When an unsuspecting hatchet fish comes along. . . wham—the jaws snap shut like a steel trap.”

“Lovely.”

> “See these brownish markings along the flank? They’re called photophores—light-producing organs. Touch the fish and its whole body lights up. Neat, huh?”

“If you say so,” she says, unimpressed, as she sucks blood from her wounded fingertip.

Brian stares at his ex-wife, the need to impress her outweighing his better judgment. “What if I told you this fish was only a juvenile? What if I told you I’ve unearthed evidence of a viper fish—as long as a school bus—that roamed the Gulf Coast millions of years ago!”

“Is that why you brought me here? To impress me with your fantasies? You’re not a scientist, Brian, you’re a hack. A bum who wasted his life collecting dead animal bones.”

She walks away, enjoying the effects of her barbs.

“Why’d you do it? Why’d you leave me for this bum? Was it the prison sentence? I know five years is a long time, but—”

“I would have left you anyway.” She pauses to light a cigarette. “All you ever cared about were these stupid relics.”

“I was an academic! It’s how I made my living!”

“Some living. We lived in a trailer.”

“So instead, you left me and took up with the very asshole who sent me to prison.”

“Don’t blame Wade. It wasn’t his fault the Feds nailed you.”

“It was his pot!”

“You agreed to hold the stuff.”

“Yeah, but you never told me how much. A hundred and fifty pounds0… Jesus, Dot.”

“I didn’t come here to listen to you whine. You said you had a proposition for us. What’s the job and how much does it pay?”

“More than even you can spend. Go get the genius and we’ll talk.”

The Trench

The Trench Generations

Generations The Mayan Resurrection

The Mayan Resurrection Vostok

Vostok Grim Reaper: End of Days

Grim Reaper: End of Days The Omega Project

The Omega Project Domain

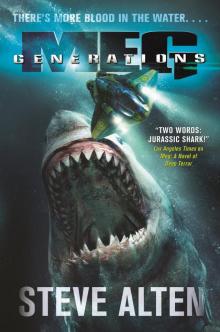

Domain Meg

Meg MEG: Nightstalkers

MEG: Nightstalkers The Mayan Resurrection mp-2

The Mayan Resurrection mp-2 Goliath

Goliath Undisclosed

Undisclosed Dead Bait 2

Dead Bait 2 Loch, The

Loch, The The Loch

The Loch The Firehills

The Firehills Sharkman

Sharkman The MEG

The MEG Phobos

Phobos Meg_A Novel of Deep Terror

Meg_A Novel of Deep Terror Meg: Origins

Meg: Origins