- Home

- Steve Alten

Generations Page 12

Generations Read online

Page 12

“Melanomas that have a low chance of traveling are less than point-one-millimeter deep; high-risk melanomas are greater than point-four. Again, yours was point-two, which was thin. I’m sure the surgeon told you this was going to have a great chance of being cured. In terms of melanoma, it can travel through the bloodstream, and the most common places for it to reappear and evolve is in the lungs and the liver.

“There are several different approaches to treat it. One is chemotherapy, and the most common chemo is a pill called Temodar. It’s easy to take, it has very few side effects, and it’s a pill you take five nights in a row, once a month. Another approach is with immunotherapy—medicines that stimulate the immune system. There are some new approaches with a medicine called ipilimumab, and that’s a possible treatment. Ipilimumab requires that you’ve had some kind of prior treatment. It’s administered by IV and it’s given once every three weeks.”

“I’ve been reading that ipilimumab had dramatic results,” Danielle said, “but it seems to be effective in only a small percentage of patients.”

“That’s correct. A third approach is something called target therapy, and that’s really where all the excitement has been.” Dr. Briggs drew a circle on a pad of paper. “I’m taking you back to high school biology. Here’s a cell, here’s the nucleus. The way our bodies work is that there are receptors on the outside of the cell, there are growth factors that circulate and trigger these receptors, and then there are a series of genes here that get turned on—it’s like the dominoes fall and the cells grow. In about forty percent of melanoma there is a broken gene called B-RAF. If you have this mutation, there are some pretty amazing drugs that target the B-RAF gene. So, if you have a broken B-RAF gene we give you a pill that blocks it—it’s like putting the brakes on it.

“You had a lentigo maligna melanoma. The most common broken gene with a lentigo maligna melanoma is something called c-KIT. I don’t know if you have a broken c-KIT gene; we’ll test for it using a liver biopsy. There is an FDA-approved medicine called Gleevec that has helped melanoma patients who have a broken c-KIT gene. So our first step is to test you to see if you have either a broken B-RAF gene or a broken c-KIT.… Hopefully you have one or the other.”

“Be honest with me, Dr. Briggs. Even under the best scenario, what are my chances?”

“With regular chemotherapy there’s a ten to fifteen percent chance the melanoma will shrink. If you get one of these targeted therapies the average shrinkage rate can be fifty to eighty percent. With Gleevec, it could be as high as forty percent if you have a broken c-KIT gene. If you don’t have a broken c-KIT gene the drug can still help, it just won’t help as much.

“Given your symptoms, my suggestion is that we start you on Gleevec right away. The traditional chemotherapy can help, but the Gleevec can be more effective.”

“With the Gleevec, how soon can we expect a response?” Jonas asked. “What are the goals here?”

“The goal is to reduce the symptoms and shrink the tumors.”

“What about a cure?”

“I’m sorry. Even with the most dramatic drugs we have, at the ten-month point, patients start to regress. There are new therapies in clinical trials, but I think Gleevec is a good first step for you.”

Dr. Briggs had started Terry on the Gleevec while they awaited the results of the tests. Meanwhile, Danielle had worked the phones, looking for alternative treatments outside of the standard cancer therapies.

They received bad news six days later: Terry’s cancer did not involve the B-RAF gene or a broken c-KIT gene, eliminating Gleevec and the options they had discussed.

However, in slamming the door it seemed God had opened a window. Dani learned about a new therapy that had recently been approved for human clinical trials for tumorous cancers—including melanoma. An appointment was made with the oncologist/hematologist overseeing the protocol; the location of the research center was just outside of Boca Raton, Florida—the very place Jonas and Terry had hoped to relocate to.

* * *

The South Florida Bone Marrow/Stem Cell Transplant Institute consisted of office suites and private hospital rooms used to treat people on an outpatient basis, as well as labs and a cryogenic facility to store stem cells.

The Taylors were ushered inside a small, cheery conference room, the walls decorated with framed medical degrees and honors in the field of oncology, hematology, and stem cell research.

The first thing that impressed Jonas about Dr. Dipnarine Maharaj was an assured calmness that could have come only from decades of experience. There was a worldliness about the man; it was in his eyes and his mannerisms, the eloquence of his voice and the intelligence conveyed in his message. For patients with life-threatening illnesses, he was the real deal—a searchlight guiding one to a life ring tossed in tempest seas, and Terry trusted him immediately.

Dr. Maharaj introduced himself and then got right to business. “I’ve reviewed your medical records, and I concur with Dr. Briggs. The cancer probably originated from the melanoma surgeons removed from your face five years ago.”

The oncologist/hematologist turned his computer’s large flat screen monitor to face them. “Terry, cancer cells are stem cells. There are different kinds of stem cells, and every organ in the body has stem cells. A characteristic of a stem cell is the way it divides into twins. One of the twins will actually begin to form tissues, while the other twin does nothing; it lies dormant. What prevents it from growing further is the immune system. As we get older or if we’re under a great deal of stress, our immune system weakens, and the cancers can grow.”

Jonas glanced at his wife. “Stress … yeah, we’ve probably had more than our share.”

Dr. Maharaj nodded. “I’m sure I can’t begin to imagine. The standard therapy for treating metastatic tumors is chemotherapy. If you look at long-term survival using the best drugs we have now, it only adds about two to three months to the average person’s survival. As a transplant physician in this outpatient setting, the chemotherapy that I give is ten times the standard dose Dr. Briggs would give. The question is, why isn’t the chemotherapy working?

“The first reason is that cancer is made up of many different kinds of cells. We have cancer stem cells, but we also have cells that are differentiating as they are dividing. Chemotherapy is designed to kill cells if they are dividing, but the cancer stem cells that are not dividing are not touched by the chemotherapy. Chemo will kill a certain number of tumor cells and those cells will shrink, so it will look as though you’re making progress, but actually curing you of the cancer requires a different approach.

“I’ve recently been approved by the FDA to begin a human clinical trial for solid tumor cancers. This protocol is based on a 1999 study conducted at Wake Forest University by my colleague, Dr. Zheng Cui. Dr. Cui discovered a cancer-resistant mouse. No matter how Dr. Cui attempted to infect this mouse with cancer, he couldn’t do it; the mouse’s immune system was simply too strong. Forty percent of this mouse’s descendants inherited the same significant cancer resistance. The white blood cells of these mice were able to seek out and destroy cancer cells not only in cell cultures, but also in living mice. Dr. Cui designed a test to measure this cancer-killing activity, called CKA, and used those cells from cancer-resistant mice to cure other mice that had cancer.

“Further investigation showed that high levels of CKA granulocytes were also found in the white blood cells of some healthy people, specifically in the immune systems of young healthy humans your daughter’s age, between ages nineteen and twenty-five.

“What I am doing is translating the basis of that clinical trial into humans. Instead of the mouse white cells, I’m using the white cells taken from the immune systems of healthy twenty-year-olds. If you take a twenty-year-old and you look at the incidence of cancer versus the incidence in a seventy-year-old, a seventy-year-old has a one hundred times greater risk of cancer. That’s because the immune system of a twenty-year-old is so much stronger. Years ago,

when the melanoma was removed from your cheek, those cancer stem cells were still there, lying dormant. When your immune system dropped, they flared up. Again, the approach here is to reverse that process.

“So, if you’re looking for an oncologist who treats a lot of melanoma patients, that’s not me. The approach I’m taking is to rebuild the immune system, because the immune system is what has broken down here. Chemotherapy further weakens the immune system. When we look at the CT scans of cancer patients using chemotherapy, the tumors are shrinking, so it appears as if we are winning the battle. In fact, we’re actually suppressing the immune system, which, in the long term, is needed to win the war.”

“Doc, how many melanoma patients have you actually treated?”

“None. But our clinical trials are for solid tumors, and this is what your wife has. To date, we’ve only treated eleven patients. Because it’s a trial, I can’t give you the results, as we’re under the strict protocol of the IND—the Investigational New Drug program. If I were to tell you all eleven patients had done well, I could be prejudicing your decision to enter the clinical trial. At the same time, one of the most important things you can do is to think positive; we know the power of the mind and how it affects the immune system. Some people might say that it doesn’t exist, but I would disagree. I have been treating cancer for a long time, and I know the people who survive are the people who say, I am going to fight this thing.”

Terry smiled. “Tell us about the protocol. What does it involve, and how soon can we get started?”

“The treatment I am using is simple: I’m basically asking a group of young people to give me some of their white cells, which I will then transfuse into you. Within these white cells are cells that are part of the innate immune system and the adaptive immune system. The innate immune system is made up of a number of white cells that are the cancer prevention system, which is actually what prevents an individual from getting cancer in the first place. The treatment is four infusions, completed over a two-week period, with the patient tested at thirty, sixty, and ninety days.”

“Are there any side effects?” Dani asked.

“With any type of transfusion, there are always some risks. Side effects can vary from a minor allergic reaction, which we can treat with hydrocortisone, to a rise in temperature. I actually prefer a rise in temperature, because the granulocytes work much better in a higher temperature, fever being the body’s natural response to infection. As for major reactions, we can prevent these through proper donor screening, but they can occur. We’ll be doing a full range of blood tests on you to find the right matches. I’m sorry, Danielle, blood relatives cannot be considered.

“As far as how soon you can begin, because this is a clinical trial we must wait until the Gleevec is completely out of your system before we can start the first treatment.”

“How long is that?” Terry asked.

“Thirty days.”

Jonas winced. “Geez, Doc, thirty days? She hardly took anything … four, maybe five pills tops.”

“I understand, and we’ll certainly utilize that time to find the best donors available. But I have to follow proper protocol procedures.”

Terry squeezed her husband’s hand. “Boca Raton is five miles to the south; maybe we could look for a place to live while we wait.”

Aboard the Hopper-Dredge McFarland

Salish Sea, British Columbia, Canada

“Nine weeks … two days … seventeen hours … thirty-six minutes, and twenty seconds.” Jason Montgomery held up his iPhone so that his aunt Trish could see the screen. “That’s how long we’ve been stuck on this stupid boat, circling a bunch of stupid rocks covered in stupid pine trees. I’d like to meet the genius who named them the ‘San Juan Islands’? Does this look anything like Puerto Rico to you?”

“Stop complaining.” Trish Mackreides reached across the galley’s aluminum prep table for the quart of milk, only to discover the container was empty. Turning down the burner under her pan of scrambled eggs, she crossed the kitchen to the walk-in refrigerator and yanked open the handle—the device falling apart in her grip.

“Monty, I thought you fixed this!”

“I did.”

“With what, a paper clip and a rubber band?”

“No. Wait, would that work?”

“Some handyman you turned out to be. I’m down to two working burners, a blender, and an oven that shuts off every seventeen minutes. And when is Cyel going to fix the plumbing? I haven’t had a shower in five days.”

“You should use the hopper; it’s just like a pool.”

“It’s salt water, Monty. Do you know what salt water does to my hair?” She turned as David entered the galley, his tinted sunglasses concealing the dark circles beneath his bloodshot eyes. “You look exhausted.”

“I couldn’t sleep. We received a report late last night that another Meg pup was netted and killed.”

“How many is that?”

“Four.”

“Another albino?”

“No, this one was one of Bela’s. Any breakfast? I need to eat, hit the head, and get in the sub before these damn fishermen slaughter another pup.”

“Sit.” Trish reached for the stove controls, reigniting the flame beneath her pan of eggs. “David, I know your priority is locating the sisters’ nursery, but you need to make time for your girlfriend. Last night, I passed by her stateroom and heard her crying.”

“To be honest, I just figured it was her menstrual cycle.”

Monty shook his head. “Junior, if that’s her menstrual cycle, I know why the plumbing is clogged.”

Trish smacked her nephew atop his head with her spatula. “Fix the handle on the walk-in and bring me a quart of milk.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“David, she’s depressed. I’ve tried to talk to her, but she’s very guarded about whatever it is that’s bothering her. Are you two having problems?”

“You could say that.”

They looked up as a rusted speaker anchored to the far wall crackled to life. “David, rezzzzt to the pilzzzzt houzzzzt.”

“I gotta go.”

“Wait.” She grabbed a plastic plate from a stack and scooped a large portion of eggs from the pan onto the dish. “Promise me you’ll talk to her later.”

David shoveled the eggs into his mouth and nodded. “Promffff.”

* * *

Captain Mohammad “Mo” Mallouh returned the intercom microphone to its stand, only to struggle to find his comfortable spot in the pilot’s chair. The red vinyl seat was worn and frayed, the foam escaping out from several holes. He had covered it with a towel, but Monty had spilled coffee on it during his afternoon shift.

A Muslim of Palestinian descent, Mo Mallouh was a product of an arranged marriage. His parents had been born and raised in Jaffa, Israel, where his father had been a respected doctor. Dr. Mallouh had moved his family to Saudi Arabia after the birth of the couple’s second child, where he ran a medical clinic in Dhahran—a compound for the Arabian American Oil Company: Aramco.

Mohammad had been born a few years later. Growing up on the Persian Gulf, the boy had spent most of his early years and summers working aboard his uncle’s hopper-dredge, keeping the deep-water channels clear of silt for the oil tankers. When he turned fifteen, Mo’s family relocated to the United States, where he graduated high school and attended Florida State University, studying to become a pharmacist. But Mohammad missed working on the water, and so he left school his junior year to join the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and received naval training. Three years later, he and his girlfriend moved to British Columbia, where he earned a decent living piloting hopper-dredges in the Salish Sea.

Mallouh had been recommended to Mac by the McFarland’s regular pilot, Matthew DeVictor, who had decided he’d had enough “thrills at sea” with the Taylor family, having spent the past three months tracking monsters in Antarctica.

David liked their new pilot, who was only twenty-seven years

old and more of a peer. The fact that Mallouh knew the Salish Sea like the back of his hand made him a valuable asset … and yet, after more than two months searching the San Juan Islands south to Puget Sound, they were no closer to locating the Megalodon nursery than when they first started—

—and now another pup was dead.

The shark, one of Bela’s, was a thirteen-foot, fifteen-hundred-pound female. Genetically identical to its mother, the juvenile killer shared the same bizarre pigment scheme—its head pure white, its dorsal surface, from its gill slits to the half-moon-shaped tail, lead gray.

According to eyewitnesses, a charter boat captain had hooked the shark for one of his paid guests while night-fishing off Orcas Island. After a three-hour struggle, they had managed to bring the big game fish to the surface and drop a net around it, only to discover they had hooked what they assumed was a great white. Unfortunately, the hook was in too deep to safely remove it. To free the line, the crew attempted to invert the shark and put it to sleep. The predator went berserk, dragging a passenger overboard, forcing the captain to kill it.

Taxidermies will not mount a protected species, and the charter boat captain couldn’t afford a hefty fine, so he turned the shark’s remains over to the Coast Guard. Suspecting it was another Megalodon pup, the authorities had contacted Nick Van Sicklen.

To demonstrate the threat the species posed to humans, the director of the Adopt an Orca program used a winch to suspend the dead shark upside down by its tail before eviscerating it with a chain saw, the contents of its stomach spilling out across a pier.

There were no human remains inside, but the YouTube video had gone viral, setting off a firestorm of protests from animal rights groups.

* * *

Exiting the galley, David made his way forward, ascending three flights of stairs to the pilothouse. The night before he had barely slept, unable to free his thoughts from the YouTube video.

The Trench

The Trench Generations

Generations The Mayan Resurrection

The Mayan Resurrection Vostok

Vostok Grim Reaper: End of Days

Grim Reaper: End of Days The Omega Project

The Omega Project Domain

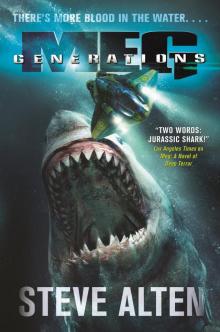

Domain Meg

Meg MEG: Nightstalkers

MEG: Nightstalkers The Mayan Resurrection mp-2

The Mayan Resurrection mp-2 Goliath

Goliath Undisclosed

Undisclosed Dead Bait 2

Dead Bait 2 Loch, The

Loch, The The Loch

The Loch The Firehills

The Firehills Sharkman

Sharkman The MEG

The MEG Phobos

Phobos Meg_A Novel of Deep Terror

Meg_A Novel of Deep Terror Meg: Origins

Meg: Origins